By: Paxton Allen and Abby Leavens

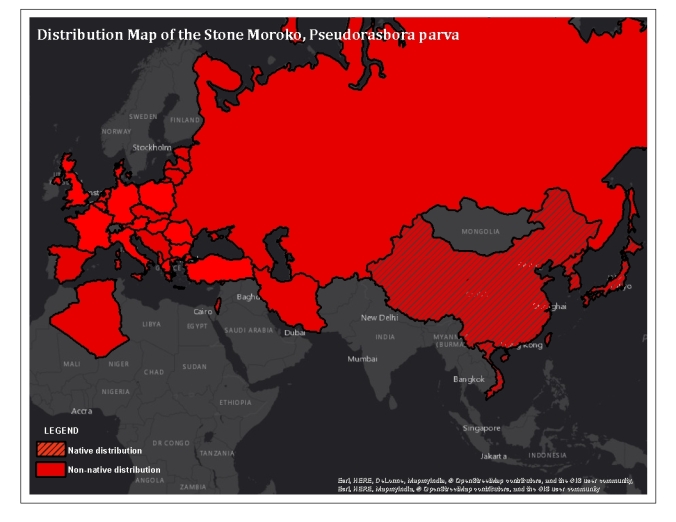

Distribution: The Stone Moroko otherwise known as the Topmouth Gudgeon is an invasive species that is native to Eastern Asia. The native range includes the Amur basin, Korean peninsula, Japanese islands, Yangtze River and Taiwan (Bänärescu 1999). The Stone Moroko was accidentally introduced to European countries sometime in the 1960’s, starting with Albania and Romania and has now been reported in 31 countries (Gavriloaie & Falka, 2006; Gozlan et al 2010). Figure 1 depicts the native and non-native global distribution of Pseudorasbora parva. There is no documentation that this species exists yet in Ontario (OFAH/OMNRF Invading Species Awareness Program, 2016).

Figure 1: Invasive and Native Ranges of the Stone Moroko, Pseudorasbora parva. From humble beginnings in East Asia, this small cyprinid has managed to invade 32 countries, making its way into Russia, and spreading westward throughout Europe to the UK and south to Israel, Iran and North Africa. It has not yet been documented in North America(Base map: ESRI, 2015; Distribution information obtained from Perdices & Doardrio, 1992; Yan & Chen, 2009; Gozlan et al. 2010; Gavriloaie, Burlaxu, Bucur, & Berkesy, 2014)

Figure 1: Invasive and Native Ranges of the Stone Moroko, Pseudorasbora parva. From humble beginnings in East Asia, this small cyprinid has managed to invade 32 countries, making its way into Russia, and spreading westward throughout Europe to the UK and south to Israel, Iran and North Africa. It has not yet been documented in North America(Base map: ESRI, 2015; Distribution information obtained from Perdices & Doardrio, 1992; Yan & Chen, 2009; Gozlan et al. 2010; Gavriloaie, Burlaxu, Bucur, & Berkesy, 2014)

Habitat: Interestingly, Pseudorasbora parva is known as a stream-dweller in Japan, but in China, it has been found to thrive in both oligotrophic and eutrophic lakes (Gozlan et al., 2010; Yan & Chen, 2009). Throughout its native, naturalized and invasive ranges, Pseudorasbora parva can live in lentic systems such as lakes, ponds, drainage ditches, slow-moving lotic freshwater systems and has even been reported in brackish systems (Gavriloaie et al., 2014). Its affinity for areas with dense submergent vegetation has been well-documented, but few other preferences stand out within the literature (Gozlan et al., 2010). The feeding habits of the species in its native range have not been studied in-depth compared to those within its invasive range (Gozlan et al., 2010). In terms of diet, it is a verified generalist, feeding on algae, plant and zooplankton, small crustaceans, benthic macroinvertebrates, as well as native fish spawn (Gozlan et al., 2010). An omnivorous opportunist, P. parva adapts its feeding habits to its life stage (limited only by the size of its mouth), and fluctuations based on the season and the ecosystem it inhabits (Gozlan et al., 2010).

Reproductive Strategy: The stone moroko (P. parva) is a small fish that reaches sexual maturity after one year and the maximum lifespan is usually three or four years (Yan & Chen, 2009; Gozlan et al., 2010; Witkowski, 2011)). Litter size is highly variable, but the average number of eggs per female per season hovers around one-thousand (Yan & Chen, 2009; Gozlan et al., 2010; Witkowski, 2011). Investment in reproduction by both males and females is unusually high in this species. Females must devote time and energy into gonadal development (Gozlan et al., 2010) in order to produce multiple litters while mature males build and guard nests (Gozlan et al., 2010; Witkowski, 2011). While this strategy is more in line with a k-strategist, the majority of P. parva’s life history traits align with an r-strategist (see Table 1 below). The species likely owes its status as an invasive species poster child to the fact that it demonstrates exceptionally high levels of genetic plasticity, habitat adaptability, and potential for population growth, while also allocating an unusually high proportion of its resources into its reproductive strategy (Gozlan et al., 2010).

Table 1: Reproductive characteristics of Stone Moroko, Pseudorasbora parva. Population growth is rapid due to early maturation and multi-litter spawning. Note that the majority of these characteristics align with r-selection, except for its high investment in parental care and reproduction, which makes its invasive vigour even more potent (Adapted from Molles & Cahill, 2014 and Parry, 1981)

| Population attribute | r selection | K selection | Pseudorasbora parva |

| Potential of population growth rate, r | High | Low | Very High |

| Life span | Short | Long | Short (3-4 years) |

| Competitive ability | Not strongly favoured | Highly favoured | Highly favoured |

| Litter size | Large | Small | Large (approx. 1000) |

| Development | Rapid | Slow | Rapid (< 1 year) |

| Frequency of Reproduction | Once to multiple times over short time period | Multiple times but over a prolonged period | Batch spawning (multiple times over short time period) |

| Offspring, body size | Many, small | Few, large | Many, small |

| Habitat | Ephemeral, unpredictable | Long durational stability, consistent | Highly variable and exceptionally tolerant |

| Resource allocation into reproductive and care of offspring | Low | High | High (multi-litter and aggressive guarding) |

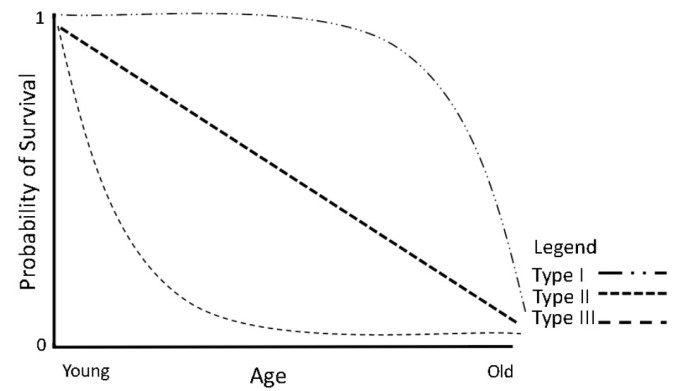

Survivorship: The Stone Moroko has a high probability of survival throughout its life making it a Type I on the survivorship curve. This species is a generalist, highly adaptable to different environments and capable of eating a wide range of food, all factors that contribute to its Type I curve. The Stone Moroko is small fish that hides in densely vegetated parts of water bodies, safeguarding it from any potential threats. Males guard eggs aggressively until they hatch ensuring the majority become fry (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2014).

Figure 2: The Stone Moroko has a Type I survivorship curve because the probability of survival is very high throughout their lives. This high probability of survivorship is due to this species ability to live in a variety of conditions and having no known predators (Adapted from Feltham, 2018).

Figure 2: The Stone Moroko has a Type I survivorship curve because the probability of survival is very high throughout their lives. This high probability of survivorship is due to this species ability to live in a variety of conditions and having no known predators (Adapted from Feltham, 2018).

Dispersal and Vectors: Humans and water constitute the primary and secondary vectors, respectively, for Pseudorasbora parva (Gozlan et al., 2010). Within its native range (Asia), the species was transported intentionally into different waterways for aquaculture as well as cultural purposes (Gozlan et al., 2010). The earliest introductions of the species into Europe occurred in the 1960s in Eastern Europe, including Romania, Albania, Hungary, Lithuania and Ukraine (Gozlan et al., 2010). In eighty percent of cases, these introductions were unintentional, when they accompanied other imported fish spawn, particularly Ctneopharyngodon idella (grass carp) (Gavriloaie, Burlacu, Bucur, & Berkesy, 2014). From there, the species spread naturally throughout Europe and into the Middle East (Gozlan et al., 2010).

Pseudorasbora parva has proven itself to be a rapid colonizer, aided by humans, but also by its reproductive strategy, biological and ecological adaptability, and its miniscule egg and body dimensions (Gozlan et al., 2010; Witkowski, 2011; Gavriloaie et al., 2014). Their introduction to Europe has been linked to imports of the ornamental fish, Golden Orfe, which is also sold in the Great Lakes. Ornamental fish are often unintentionally released by aquarium owners into sewage and drains which allows for the species to be introduced into streams and rivers (Copp et al, 2010). Humans are beneficial to the Stone Moroko as they are the main means of dispersal. Since there are no barriers known for this species, if it were to enter the Great Lakes water system, eradication would be a difficult task.

Table 2: The main vectors enabling the range expansion of Pseudorasbora parva (from Copp, 2007)

| Source | Notes | Long Distance | Local |

| Aquaculture Stock | All life stages as contaminants | Yes | Yes |

| Bait | Juveniles and adults | Yes | |

| Pets and aquarium species | All life stages as contaminants | Yes | Yes |

| Water | All life stages by natural dispersal | Yes | Yes |

Special Considerations: There is evidence to suggest that Pseudorasbora parva acts as a host, intermediate host, 2nd intermediate host and healthy carrier of parasites within both its native and invasive ranges, although fewer such species occur within the invasive range (Gozlan et al., 2010). This species has been know to be a vector of the Oriental live fluke which can infect humans (OFAH/OMNRF Invading Species Awareness Program, 2016). Within the invasive range, two parasites of particular concern are Anguillicola crassus, which affects eels, and Sphaerothecum destruens, affecting salmonids (Gozlan et al., 2010). Given that eels are already a species of special concern in Canada, and that salmonids are an important food source and predator within our oceans and lakes, and that P. parva can carry these pathogens without any symptoms, its introduction into Canada’s waterways may lead to irreparable harm.

Pseudorasbora parva has also been shown to alter trophic dynamics in several countries because it competes with native fish species, and can even change the abundance of certain flora and fauna (especially other piscifauna). Within invaded ecosystems, it will populate rapidly and require more food sources, thereby accelerating plant and plankton growth (Gozlan et al., 2010; Witkowski, 2011).

___________________________________________________________________________________________

References:

Adámek, Z. and Siddiqui, M.A. (1997). Reproduction parameters in a natural population of topmouth gudgeon Pseudorasbora parva, and its condition and food characteristics with respect to sex dissimilarities. Polish Archives of Hydrobiology 44, 145–152.

Arnold, A. (1990). Eingebürgerte Fischarten: Zur Biologie und Verbreitung allochthoner Wildfische in Europa [Naturalised Fish Species: Biology and Distribution of Non-Native Wild Fish in Europe] (in German). A. Ziemsen Verlag, Wittenberg, Lutherstadt.

Asaeda, T., Priyadarshana, T. and Manatunge, J. (2001). Effects of satiation on feeding and swimming behavior of planktivores. Hydrobiologia 443, 147–157.

Bänärescu, P. (1999). Pseudorasbora parva (Temminck et Schlegel, 1846). In: The freshwater fishes of Europe. Vol. 5/1, Cyprinidae 2/1, AULA-Verlag GmbH, Wiebeisheim, pp. 207-224.

Copp, G.H., L. Vilizzi, and R.E. Gozlan. (2010). Fish movements: the introduction pathway for Topmouth Gudgeon Pseudorasbora parva and other non-native fishes in the UK. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 20:269-273. dx.doi.org/10.1002/aqc.1092.

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. (2018). Topmouth Gudgeon, Pseudorasbora parva. Retrieved from GB non-native species secretariat: http://www.nonnativespecies.org

Froese, R. and D. Pauly. Editors. (2011). Pseudorasbora parva. FishBase. http://www.fishbase.us/summary/Pseudorasbora-parva.html.

Gavriloaie, C., Burlacu, L., Bucur, C., & Berkesy, C. (2014). Notes concerning the distribution of Asian fish species, Pseudorasbora parva, in Europe. Aquaculture, Aquarium, Conservation & Legislation – International Journal of The Bioflux Society (AACL Bioflux), 7(1), 43-50.

Gavriloaie I. C., Chiş I. E. (2006). [Considerations regarding the present situation of species Pseudorasbora parva (Temminck & Schlegel, 1846) (Pisces, Cyprinidae, Gobioninae) in Romania]. Drobeta, Şt Nat 16:123-133. [in Romanian].

Gavriloaie I.C., Falka I. (2006). Consideratii asupra raspândirii actúale a murgoiului baltat – Pseudorasbora parva (Temminck & Schlegel, 1846) (Pisces, Cyprinidae, Gobioninae) – în Europa [Some considerations concerning the present distribution of the topmouth gudgeon – Pseudorasbora parva (Temminck & Schlegel, 1846) (Pisces, Cyprinidae, Gobioninae) – in Europe]. Brukenthal Acta Musei I.3:145-151 [in Romanian].

Gozlan R. E., Andreou D., Asaeda T., Beyer K., Bouhadad R., Burnard D., Caiola N., Cakic P., Djikanovic V., Esmaeili H. R., Falka I., Golicher D., Harka A., Jeney G., Kovác V., Musil J., Nocita A., Povz M., Poulet N., Virbickas T., Wolter C, Tarkan A. S., Tricarico E., Trichkova T., Verreycken H., Witkowski A., Zhang C. G., Zweimueller I., Britton J. R. (2010). Pan-continental invasion of Pseudorasbora parva: towards a better understanding of freshwater fish invasions. Fish and Fisheries 11:315-340.

Hanazato, T. and Yasuno, M. (1989). Zooplankton community structure driven by vertebrate and invertebrate predators. Oecologia 81, 450–458.

Hliwa, P., Martyniak, A., Kucharczyk, D. and Sebestyén, A. (2002). Food preferences of juvenile stages of Pseudorasbora parva (Schlegel, 1842) in the Kis-Balaton Reservoir. Archives of Polish Fisheries 10, 121–127.

Janković, D. and Karapetkova, M. (1992). Present status of the studies on range of distribution of Asian fish species Pseudorasbora parva (Schlegel) 1842 in Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. Ichtyologia 24, 1–9.

OFAH/OMNRF Invading Species Awareness Program. (2016). Stone Moroko. Retrieved from Ontario’s Invading Species Awareness Program: http://www.invadingspecies.com/stone-moroko/

Pinder, A., and R.E. Gozlan. (2003). Sunbleak and Topmouth Gudgeon-two new additions to Britain’s freshwater fishes. British Wildlife 15(2):77-83. http://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/7917/1/sunbleak_&_topmouth_gudgeon.pdf.

Priyadarshana, T., Asaeda, T. and Manatunge, J. (2001). Foraging behaviour of planktivorous fish in artificial vegetation: the effects on swimming and feeding. Hydrobiologia 442, 231–239.

Rosecchi, E., Crivelli, A.J. and Catsadorakis, G. (1993). The establishment and impact of Pseudorasbora parva, an exotic fish species introduced into Lake Mikri Prespa (North-Western Greece). Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 3, 223–231.

Sunardi, A.T. and Manatunge, J. (2005). Foraging of a small planktivore (Pseudorasbora parva: Cyprinidae) and its behavioural flexibility in an artificial stream. Hydrobiologia 549, 155–166.

Sunardi, A.T. and Manatunge, J. (2007). Physiological responses of topmouth gudgeon, Pseudorabora parva, to predator cues and variation of current velocity. Aquatic Ecology 41, 111–118.

Sunardi, A.T., Manatunge, J. and Fujino, T. (2007). The effects of predation risk and current velocity stress on growth, condition and swimming energetics of Japanese minnow (Pseudorasbora parva). Ecological Research 22, 32–40.

Well written and very informative. Great use of peer reviewed references. Map is quite good and while the lines help, perhaps another colour to indicate their native area would make it easier to see. Under the special considerations section – what’s the difference between host, intermediate host, and 2nd intermediate host?

Roni

LikeLike