In March 2024 the University of Illinois Chicago announced that an NIH grant of $2.4 million will support UIC researchers as they bring a vaccine against elephantiasis to clinical trial. Professor Ramaswamy Kalyanasundaram, head of the UIC Medicine Rockford Department of Biomedical Sciences, is working towards the development of the first vaccine for lymphatic filariasis, which affects “more than 100 million people” worldwide. The grant is part of the NIH Small Business Innovation Research programme and will contribute to final studies required for investigative new drug approval from the FDA.

Elephantiasis

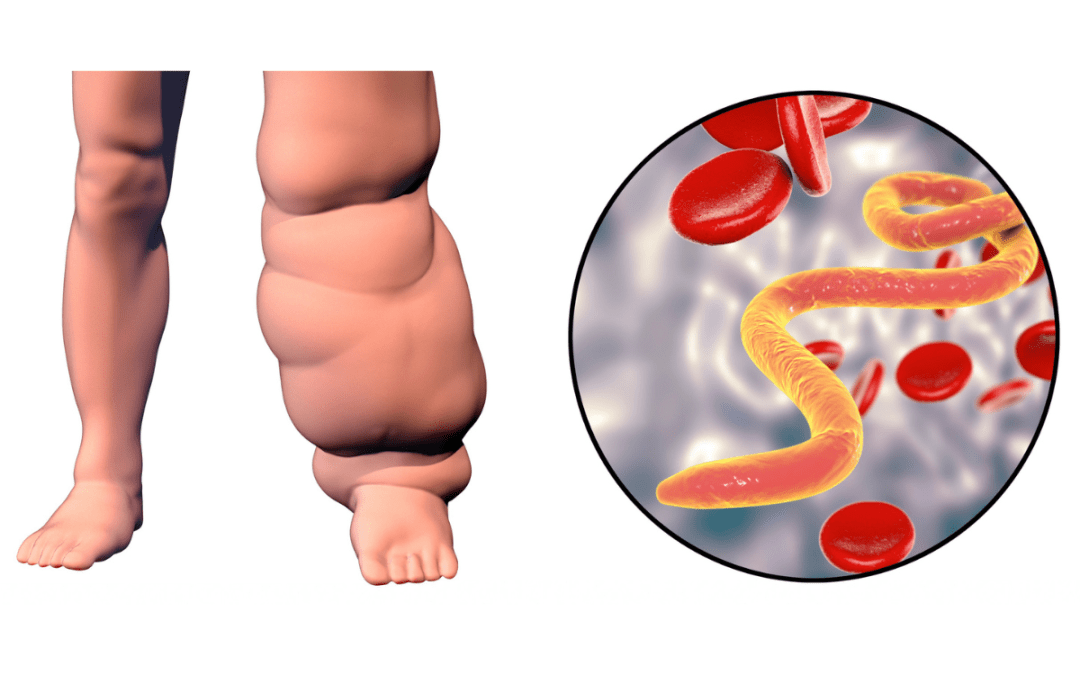

WHO describes lymphatic filariasis, also known as elephantiasis, as a “painful and profoundly disfiguring disease” caused by infection with nematode parasites in the Filariodidea family, transmitted through the bites of infected mosquitos. Mosquito-transmitted larvae are left on the skin, from where they migrate to the lymphatic vessels to develop into adult worms and continue a cycle of transmission.

In communities where filariasis is transmitted, “all ages are affected”, and it has a “major social and economic impact”. Lymphatic filariasis affects “over 120 million people” in 72 countries across the tropics and sub-tropics of Asia, Africa, the Western Pacific, and parts of the Caribbean and South America.

The CDC describes the disease as a “leading cause of permanent disability”, commenting that communities “frequently shun and reject” people who have been disfigured. Affected people are unable to work because of the disability, which “harms their families and their communities”.

A desperate need

Professor Kalyanasundaram emphasises that a vaccine is urgently needed, as medications for lymphatic filariasis are proving ineffective. Despite efforts to provide medication to areas where the disease is endemic, infections persist in many regions. In 2015, he spent five months in India to evaluate these efforts, finding that many people continue to suffer from the disease.

“There’s medicine available, but the medicine does not completely cure the infection and not everyone has access to or will take the drugs.”

Thus, a single shot vaccine that offers at least a year of immunity, is a promising alternative.

“If we have a vaccine, wherever you suspect that not everybody is taking the medication, you can at least give a shot and then they will be protected for at least a year.”

A long journey nears fruition

Professor Kalyanasundaram began working towards this goal in the 2000s as part of the WHO Genome Project and identified the parasite genes that “manipulate” the host’s immune system to evade a response and survive in the human body. His research group then identified vaccine antigens by finding which antibodies in the blood of naturally immune people protected against the genome.

“I’ve had several postdoctoral research associates and graduate students work on the project over the past 20 years. All of our work is finally coming to fruition.”

The team was able to identify potential targets and have tested these in preclinical studies for two decades. A previous NIH grant enabled PAI Life Sciences in Seattle to help with scale up of production of the current vaccine formula: a “combination of three antigens to induce a prolonged immune response that wards off infection”. This grant will fund toxicology studies and other final steps.

“We’re hoping that in the next three to five years, the vaccine should be ready for actual human immunisation.”

Neglected diseases such as elephantiasis will be considered during our keynote panel on priority pathogens and the inclusion of neglected diseases in a global strategy to tackle them; you can get your tickets to join us for this here, and don’t forget to subscribe here.