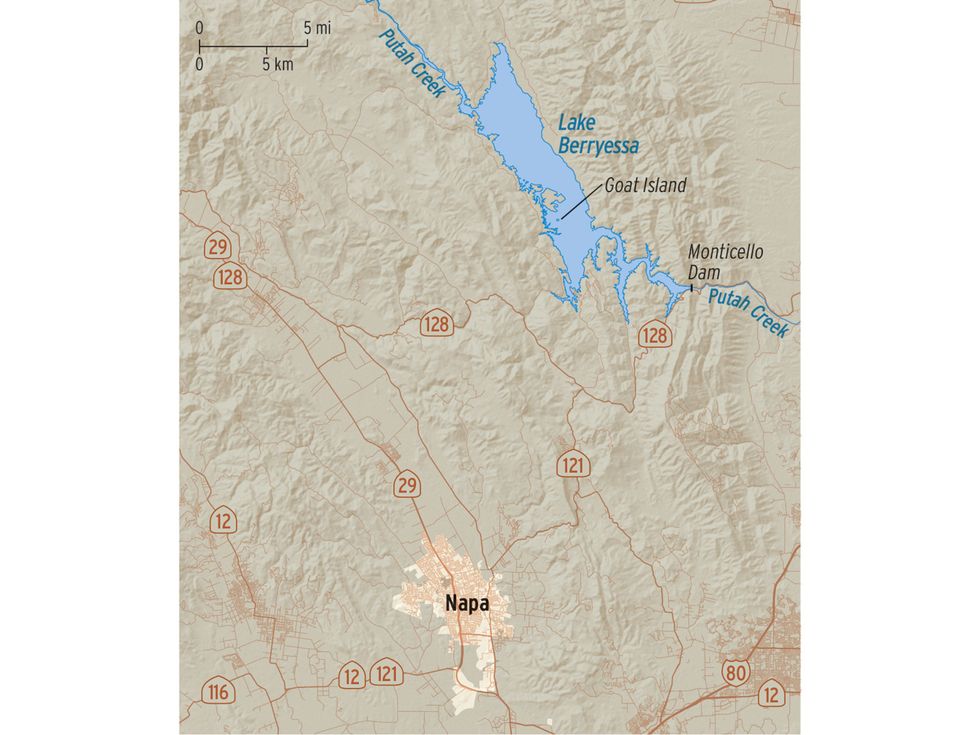

Goat Island in Lake Berryessa pokes up from the water like the crown of a hat. Beyond it, the hills are unusually triangular, coming to soft peaks instead of rolling mounds. Standing on the shore, I tried to imagine the island as it had been 62 years ago: not an island at all but the top of a hill. The lake is man-made, the result of a dam built across Putah Creek. The 1.6 million acre-feet of water cover a fertile valley and a town named Monticello.

The idea that there’s a town under a lake in Napa County, an hour-and-a-half drive from my house, was intriguing. Add to that the fact that Dorothea Lange, whose photographs humanized the Great Depression, shot a series on the flooding of the valley and the town, and I knew I had to see Lake Berryessa.

This article was featured in Alta Journal's free Weekend Read newsletter.

SUBSCRIBE

When we drove up to the lake, I was pleasantly surprised. Even though it was Memorial Day weekend, the beach wasn’t crowded. Children splashed in the water, and Canada geese bobbed near the shore. The park ranger greeted us with a list of freedoms. We could swim, boat, fish, and picnic here, he said. Parking was free. Have a good time.

Soon my husband, son, and I were gliding toward the island in our inflatable raft. In the distance, speedboats tore through the water, but the lake is large—23 miles by 3 miles—so the wake rarely disturbed our placid progress. I looked into the water as if I expected to see houses submerged below. All I saw were grebes, waterbirds with crimson eyes that would suddenly dive down and swim so far, so fast, they seemed to disappear.

Berryessa Valley was named after Jose Jesus and Sisto Berryessa, two brothers who obtained a Mexican land grant of about 36,000 acres in 1843. They built a 90-foot adobe and raised cattle and horses, but had to slowly sell off the land to pay gambling and other debts. In 1860, the last plot was auctioned off for $1,653. Monticello was founded six years later. In the 1950s, when the dam was being built, the town had a hotel, a general store, a restaurant, two gas pumps, and a cemetery. Around 300 people lived there, mostly ranchers and farmers, many of them related. While Napa wasn’t yet known for wine, by all accounts the soil was remarkably productive. Locals grew alfalfa, grain, grapes, pears, and walnuts. By the time the dam opened in 1957, crops had been torn out and residents forced from their homes. Today, Monticello Dam provides water to Solano County.

Goat Island had recently been a nesting ground for Canada geese. On the hilltop, I counted eight abandoned nests covered with eggshells and feathers. Later we spotted four goslings scooting behind their parents around cottonwood trees sticking up near the shore. In drier years, when the water level drops, the trees grow in the fertile lake bed, shooting up 30 to 40 feet. When the water rises again, they are partly submerged and become bass habitat. Two fishermen were floating beside one of these trees in a small boat. As we passed, a fishing pole bent and a moment later, they scooped up a large bass in a net. The man who’d caught it hooted, and threw up his fists in triumph. We applauded. “Thank you, everyone, thank you God, thank you to you,” he shouted.

Lake Berryessa is full of oddities like the half-drowned cottonwood trees. Excess water drains to the other side of the dam through the so-called Glory Hole, a 72-foot-diameter spillway that looks like a surreal hole has formed in the lake. While Monticello is gone, a bridge that once spanned Putah Creek remains. In 1995, the water fell so low that the bridge was exposed, and people rode their horses across it.

In another peculiarity, a legal settlement allows one local family to pasture its cattle on the land around the lake forever.

“That family, in perpetuity, can graze their land, plus our land, in the lake flow,” says Emmett Cartier, outdoor recreation planner with the Bureau of Reclamation, which manages dams, power plants, and canals throughout the West. “And they do. So there are cows out there in the bed of Lake Berryessa.”

These strange occurrences underscore what happens when people change the ancient course of a valley. Weirdness tends to pop up, like ripples of pushback against the relatively new normal.

In 1956, Life magazine paid Dorothea Lange $1,000 to shoot a series on the flooding of Berryessa. Lange, who proposed the project, was familiar with Napa, having taken painting trips there with her first husband, artist Maynard Dixon. Her eye-opening political photographs include Migrant Mother, an iconic image of the Great Depression. Depicting everything from southern sharecroppers to Japanese internment camp prisoners, Lange’s work put a human face on injustice. With Berryessa, she wanted to emphasize the toll the dam would take, not only on people, but on the environment, too. This unusual emphasis for the 1950s signaled the influence of her second husband, agricultural economist Paul Taylor.

“He was very much an environmentalist and no doubt helped her understand that there were environmental costs to dam building,” says Linda Gordon, author of Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits. “It’s quite extraordinary and prescient of her to focus on environmentalism at that period of time.”

Lange enlisted fellow photographer Pirkle Jones to accompany her to the valley. They made multiple trips in 1956 and 1957. According to Milton Meltzer’s book Dorothea Lange: A Photographer’s Life, it was “exhausting work.” It was hot, and Lange, who suffered from intestinal problems including ulcers, was “in one of her poorer periods.” Unable to eat, she looked “so tiny and weak Jones wondered how she could go on with the job.… She might be running a high fever, but still she’d insist on going ahead. Only when she was at the point of collapse could she be forced to stop.”

The resulting 175 photographs were rejected by Life, which instead published a piece about a flood in Texas. In 1960, the Death of a Valley series was printed in Aperture, a magazine devoted to photography that Lange, Ansel Adams, and others founded.

Since that issue of Aperture is out of print, finding the series all in one place proved difficult. The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art owns many of the photographs, but they’re not on display. So on a warm morning, in a room under a parking garage behind the museum, I met up with Shana Lopes, an assistant curator of photography at SFMOMA. She led me through a maze of cement hallways to see the photographs, which she’d brought out of storage. In the study room, they were waiting on wooden shelving in white mats. Lopes removed the tissue paper covering the images. “I feel like people don’t realize they can use museums this way,” she said. “That’s what museums are supposed to do with the art—share it.”

Immediately, I recognized the hilltops I’d seen behind Goat Island. The photo I was looking at was an image of Monticello taken by Jones. While the triangular peaks are in sunlight, most of the valley is in shadow, as if to prefigure the massive amount of water that will soon cover it. The town sits at the base of the hills, a pastoral cluster of white homes, barns, and trees. An orchard grows in the distance, and a freshly plowed field is in the foreground. Tree-lined Putah Creek—which was more of a river—flows through the valley.

Lopes also showed me the Death of a Valley issue of Aperture. The uncredited text calls what happened to the valley “orderly destruction—scheduled down to the last fence post.” Everything was removed. Houses were relocated or burned. Concrete structures leveled. Trees were cut down, bushes dug up, grapevines removed. Lange and Jones photographed it all.

The series moves fearlessly through the destruction. There are the before pictures: a woman in a field of poppies extending her arm for a handshake, a white farmhouse with a vibrant, blooming garden. “Visible changes came slowly and quietly,” the Aperture text reads. “There was packing, selling, moving. Families disappeared, melting away, emptying the valley.” Jones’s photograph of the last harvest shows a Mexican worker holding a wooden box overflowing with plump grapes—the accompanying text says that 850 tons were used by “one of California’s finest wineries.” The vibrant grapevines behind the worker will soon be ripped out. In a similar display of waste, Jones captured three men cutting down an enormous oak tree with graceful, lacy branches. The tree, which is so big that the men look like insects, is about to topple over.

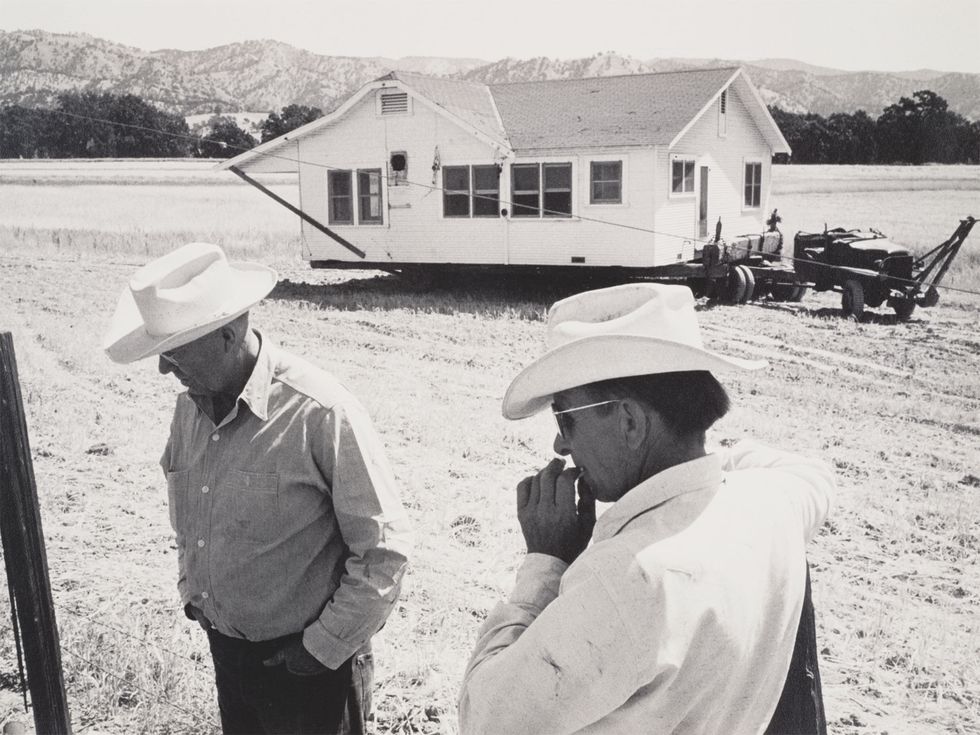

The human impact is also evident. In one photo, a tractor drags a white house on a rolling platform through a field. In the foreground, two men in cowboy hats are turned away, as if they don’t want to watch. Their body language is bent, resigned, sad. In another photograph, a couple walk through the cemetery with their backs to the camera. The woman appears to be holding flowers. Soon the graves will be dug up and the bodies moved to a new cemetery.

As the “government men” came in, the demolition sped up. “Catastrophe came to the old Berryessa Valley,” the text reads. “Fires burned. Dust and smoke filled the air.… The valley is black at night.” Lange’s portrait of a bulldozer highlights the blades in front so that, gleaming, it emerges from the dust like a monster. Another photograph shows desolation—a pile of debris in an empty field, three figures barely visible in the distance. Then the rains came, and Jones and Lange were there, photographing water creeping over the bleak landscape. Lange’s picture of 304-foot-high Monticello Dam is taken at night from far away. It’s lit up so that it seems to glow with malevolent light.

Death of a Valley is a powerful, eloquent witness to destruction. Perhaps the most poignant photograph is one that Lange took of a white horse running through a barren field. Its eyes are deadened, as if it’s running because it doesn’t know what else to do. It’s a metaphor for a community being displaced. The accompanying text reads, “The animals were terrified.”

Berryessa Valley has a history of displacement. At least 12,500 Native Americans lived in the area before European contact, according to the Bureau of Reclamation. These early inhabitants were driven out by settlers, sent to California missions, or sickened by smallpox and other diseases. Studies show that at least 100 archaeological sites are covered by the lake, notes Cartier. “Nowadays we wouldn’t do that,” he says.

Discussions about damming Putah Creek increased in the 1940s and ’50s, along with the population. Solano County, on Napa’s eastern border, was booming, agriculture was expanding, and the water supply was limited. Many in Napa were against the $37 million dam, which would flood one-eighth of their county’s agricultural land and yield them no water. The issue was debated for years, but then the military got involved. Solano County was home to Mare Island Naval Yard, Benicia Arsenal, and Travis Air Force Base.

“One of the turning points, I think, was that in the postwar world, during the Cold War, the military in Solano wanted a reliable water supply,” says Cartier. “And they didn’t feel like they were getting it from the groundwater and the [Sacramento River] delta, which can be salty. So at Travis Air Force Base, when they asked the commander, do you need a water supply, he weighed in heavily.”

By the time the dam opened, an article in the San Francisco Examiner had declared Lake Berryessa “the vacation home of thousands of sportsmen.” Some 60,000 people had already visited the lake that summer, it said, and “even larger crowds are expected next season.” Progress, the article implied, had been achieved.

When I called Murray Clark’s home in Red Bluff, California, his wife told me he was out mowing. A few hours later, he called me back. Now 86, Clark grew up in Monticello. It was “a kind of a rough-and-tumble town,” he said. “There was no law. You just kind of done anything you were big enough to do…. It was Wild West–like.”

Clark was 23 and married with two children when he was forced from his 600-acre ranch. His family had lived in Berryessa Valley for four generations. His great-grandfather, Abraham Clark, settled there in 1866 and at one point owned 10,000 acres. Clark’s dad, Howard, grew “tremendous crops of grain.” They were dry-farmed, meaning no irrigation. The rain provided plenty of water.

When Clark first heard about the dam, he wasn’t worried, because they’d been talking about it since the 19th century. To those living in the valley, it seemed absurd that the state wanted to remove every tree, bush, and building to make a lake.

“It was just a way of life, and everybody had their homes, and we had a pretty good store there and two or three bars and big rodeos, and you just didn’t think they’d take all that away,” he said. “But they sure as hell did.”

When I asked what it was like to leave Berryessa Valley, Clark choked up.

“Excuse me,” he said.

“Oh, I’m sorry,” I said. “I’m so sorry.”

“It still bothers me. My dad still lived in the same house he was born in when the dam went in, so it was really hard for him.”

There was a pause.

“It was a hard process for everybody,” he went on. “I mean, we were mostly all related, cousins and uncles and aunts, and everybody was just kind of on their own. Some of them I never saw again.”

After leaving the valley, Clark moved around a lot. He worked for Standard Oil, as a boilermaker apprentice, and for Kaiser Steel. He tried his hand at cowboying but “starved to death. I loved it, but I just couldn’t support my family.” Finally he got work as a pipe fitter, a job that stuck. Recently he received an award for 50 years in the pipe fitters union.

While the government paid his family for the land, it wasn’t enough. They went to court and were awarded another $90,000. However, Clark feels that the money is beside the point. “Money don’t replace those things,” he said.

I thought about what it means to be displaced. It often means more than losing a home. It can mean a loss of history, culture, and identity. Clark, the youngest of six children, is the last surviving member of his family. His description of leaving the home where his father was born and the land his great-grandfather settled made me think of one of Lange’s images from Death of a Valley.

In an empty house, Lange found two black-and-white photographs lying in the upstairs hallway. They were the only things in the house, except for a few schoolbooks, brass knobs, and wooden curtain rods. One photo was of a woman, the other of a man; both of them appear to be from the 19th century. The woman wears a white cap and a high-necked black dress with a broach at her throat, and the man has a thick beard. The text calls the pictures “relics—signs of severed roots.” Lange photographed them where they lay, forgotten relatives about to be buried by water.•

Joy Lanzendorfer’s first novel, Right Back Where We Started From, was published in 2021. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, Raritan, the Atlantic, NPR, Ploughshares, Poetry Foundation, and others.