Feature: The changing face of Big Science

CERN wasn’t built in a day

Large research infrastructure is expensive and complex, and difficult to fund and to coordinate. For the past ten years, ‘roadmaps’ have aimed at facilitating the design side of things. But, so long as long-term vision is lacking, the sustainability dimension is often overlooked.

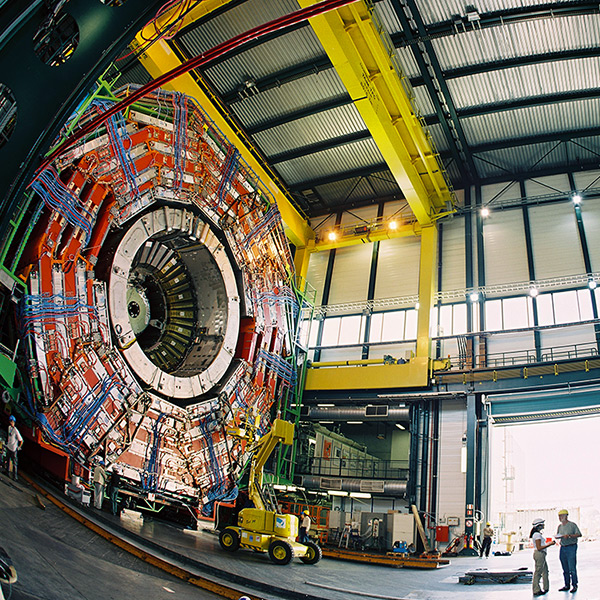

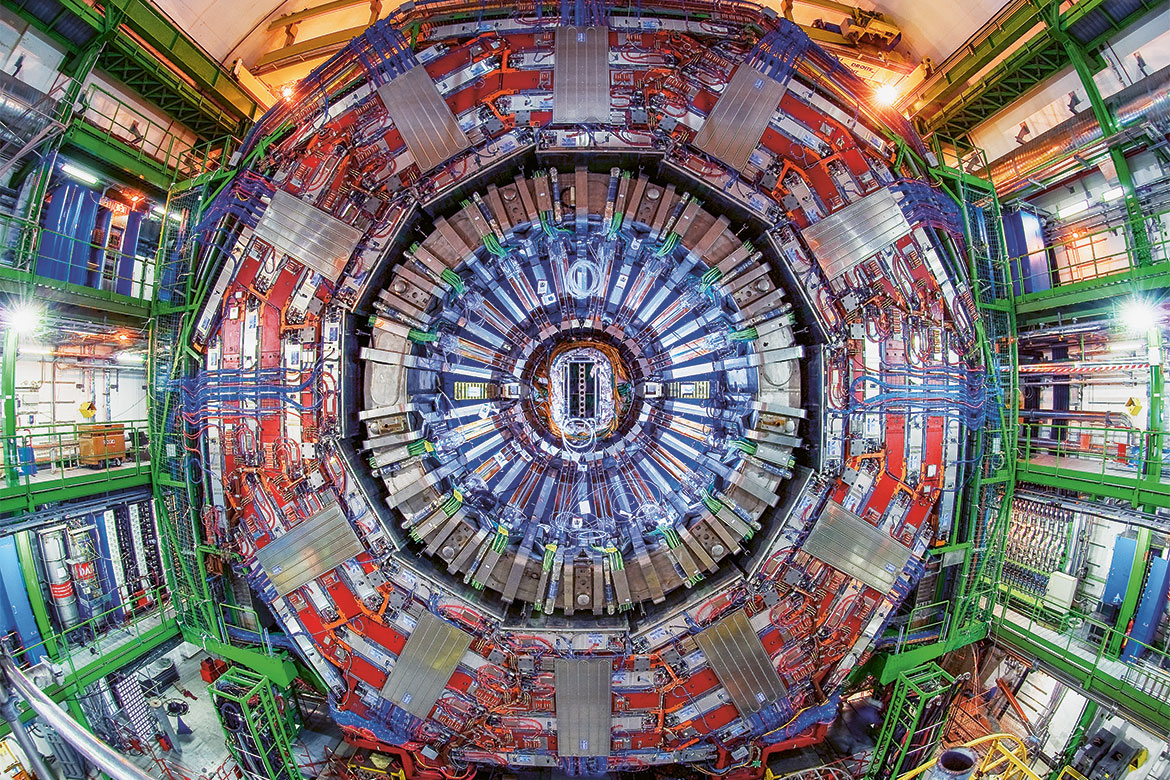

With its 22 member countries, CERN is a ponderous organisation. New legal forms are more flexible, but also less stable. | Image: Maximilien Brice/CERN

We spent four billion francs on the Hadron Collider at CERN, two on the European Spallation Source in Sweden. Then there is the 275 million on the SwissFEL in Aargau, not to mention all the biobanks and other digital databases. It takes a lot of money to build the infrastructure needed to conduct multiple instances of cutting-edge scientific research. For decades, too, it can remain tied up. Hence a simple question: who has the final word as to whether to finance these megaprojects? The answer to that is yet more complicated.

The world of politics is paying ever greater attention to large research infrastructure, in particular the United States and the European Union, but also within the OECD and the G7. The EU now considers it as an ‘engine’ for the economy. With its European Strategy Forum on Research Infrastructures (ESFRI), it has endeavoured to craft strategic prioritisation procedures. First rolled out in 2006, the ‘roadmaps’ are the result of collaboration between scientists and representatives of the European Commission, of EU Member States and of countries associated with the Framework Programmes for Research and Innovation, including Switzerland. The essential components of a roadmap include: an inventory of existing infrastructure, a needs assessment, and definitions of future priorities.

Global competition

“Europe’s will for greater coordination has emerged out of a landscape of rising costs and mushrooming projects and in a climate of national budgetary cutbacks”, says Nicolas Rüffin, a specialist in scientific diplomacy at the WZB Social Research Centre in Berlin. But it can also be linked to the perception of increased competition at the global level: the argument is that if European countries don’t pool their resources, they’ll be unable to compete with the United States or Asia”.

Most European countries have decided to follow the ESFRI model, says Isabel Bolliger, who studies research infrastructure at the Swiss Graduate School of Public Administration (IDHEAP) in Lausanne. “Every State has integrated the European methodology but in its own way, according to the structure of its institutions, its science policy and its political culture. As a result, there is a wide variety of models, ranging from the simple identification of missing infrastructure to detailed recommendations for budgetary decisions”.

The first Swiss roadmap, drawn up in 2011, “serves primarily as a planning tool for the Confederation and the universities”, says Nicole Schaad, the head of national research at the State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SEFRI). National research projects first undergo pre-selection by the ETH Board and Swissuniversities, the Swiss university association. They are then evaluated by the SNSF on the basis of their scientific quality. “The Swiss model has a certain complexity, due to the central roles played by the ETH Board, which is linked to the Confederation, and by Swissuniversities, which represents cantonal institutions”, says Bolliger. “But the inclusion of these actors ensures the commitment of the institutions”.

Roadmaps create coherence

Scientists often see the Swiss roadmap as a funding instrument: but it’s not. “It should be noted that the Confederation only plays a secondary role in national infrastructure, as it does not have a specific budget”, says Schaad. “The parliament votes on a global amount for universities. That includes both teaching and research. The universities then decide on how to allocate it. It’s only when it comes to intergovernmental infrastructure that the Confederation has a say on whether to participate in a particular project. And the selection of this type of project is also the direct responsibility of the SEFRI, which studies the proposals of the scientific communities concerned and a position paper from the SNSF.

Some national roadmaps do encompass funding, in Sweden and the Czech Republic, for example. According to Bolliger, “this makes it easier to manage national resource allocation priorities. But the Swiss model is defined by the overarching federal system, hence there is no national budget line for research infrastructure. And at the same time, the country reaps the benefits of having highly autonomous universities”.

Coordinated by the Swiss National Science Foundation, the European InRoad project aims at identifying the best practices in terms of research-infrastructure planning, harmonising procedures and encouraging the sustainability of facilities. In particular, it has gathered extensive data from EU Member States and countries associated with Horizons 2020. InRoad’s results will be published at the end of 2018. Alongside other young European scientists, Isabel Bolliger of the IDHEAP in Lausanne has co-founded the BSRI network, which is currently collecting contributions for a book.

The roadmaps have introduced greater procedural consistency. “Previously, when a community of scientists had an idea, they would just approach the SEFRI and politicians”, says Hans Rudolf Ott, a professor of physics at ETH Zurich, who has been involved in planning several large research infrastructure projects. “Today, the files must be well prepared, the objectives and milestones clearly defined, and the financial needs assessed. It takes a lot of work, but it’s ultimately more efficient”. For Ott, these procedures make it possible to establish a constructive dialogue between scientists and institutions. “There is a forum where we can express our opinions, which are heard by the institutions. In turn, they draw our attention to certain political and financial aspects that could compromise the feasibility of the project”.

Still according to Ott, the perceived burden of the processes outweighed the motivation of the members of scientific communities to go through with them. “But they have quickly come to appreciate the benefits, because the roadmaps allow them to work upstream and thereby define priorities. This certainly means giving up on some projects, but the worst would be to lock horns with policy makers, which would probably mean getting nothing at all”.

New legal entities

One unresolved issue is the sustainability of research infrastructure. The design, construction and use of these installations span decades, and prior funding must be earmarked for running costs, modernisation, and decommissioning where applicable. “Finding adequate financial resources is a challenge for many infrastructure projects and a real threat to medium and long-term planning capacity”, according to a 2017 OECD report on the subject co-authored by Ott.

“At the moment, obtaining guarantees for such long-term financing remains very difficult”, says Bolliger. “The policy cycle is generally one year, and at best four. Hence there is more incentive to build new installations than to budget for the operation and maintenance of a project. But this is essential if we want to guarantee the primary objective of these infrastructures, namely scientific excellence”.

This is due in particular to the increasing complexity of the institutional arrangements for projects and their multiple sources of funding. “With a view to managing this, new legal forms have emerged, such as the European Research Infrastructure Consortium, or ERIC”, says Rüffin. “These streamlined entities are more flexible than large organisations such as CERN. But they also generate instability and increasing complexity”. The European Union launched the ERIC in 2008 to enable the rapid creation of research infrastructure. It’s a legal framework that provides for the formation of associations of States and intergovernmental organisations, without having to return to lengthy negotiations every time. Under an ERIC, a State may delegate a private or public entity to represent it. This could be a research organisation, for example. But the State remains ultimately responsible. “The 19 consortia currently in existence differ greatly”, says Maria Moskovko of Lund University in Sweden, who is studying how they work. “Some are large installations concentrated in one place, while others are organised in a network. As the legal form is new, they are facing problems with civil services and banks, which do not understand what they really are”.

There is currently a poor understanding of the new legal entities that have been implemented over the last decade, as is the case with the constellations of actors and the dynamics of decision-making. But one thing has become clear: global reflection is now needed to determine which common methodologies and models work best.

Geneviève Ruiz is a freelance journalist and lives in Nyon (VD).