By Koaw 2023,

BEST FEATURES FOR ID: (All of these features are discussed below in detail.)

Check if the cheek is mostly scaled and the operculum is only partially scaled.

Get a count on the submandibular pores.

Get a count on the branchiostegal rays.

Get a count on the lateral line scales.

Examine the patterning.

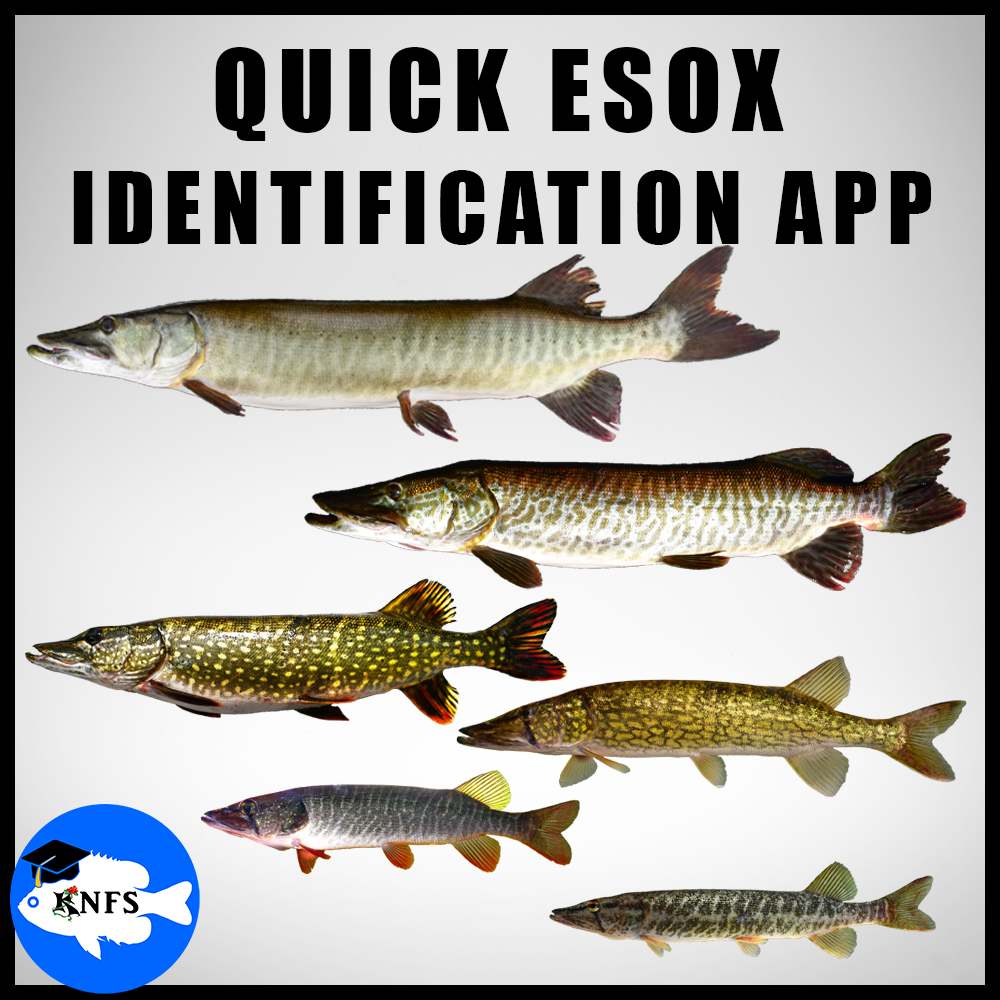

Try the Quick Esox ID App that may offer a fast analysis, if needed.

Although color and patterning are very useful to assess when identifying the species within the genus Esox, features that are countable (meristic) and measurable (morphometric) are more reliable, and as such, are the focus of this guide. It’s important to examine more than one feature for confident IDs.

INTRO: The northern pike (Esox lucius) is member of the genus Esox, the pikes. [1] [2] This lie-and-wait predator is a circumpolar species, found in the mostly cool & cold waters within the Northern Hemisphere of North America and Eurasia; (range discussed more in “LOCATION” down below.) Between 2011-2014, two new species have been separated from the northern pike in the southern parts of Europe, Esox cisalpinus and Esox aquitanicus. [3] [4] [5]

Click to enlarge.

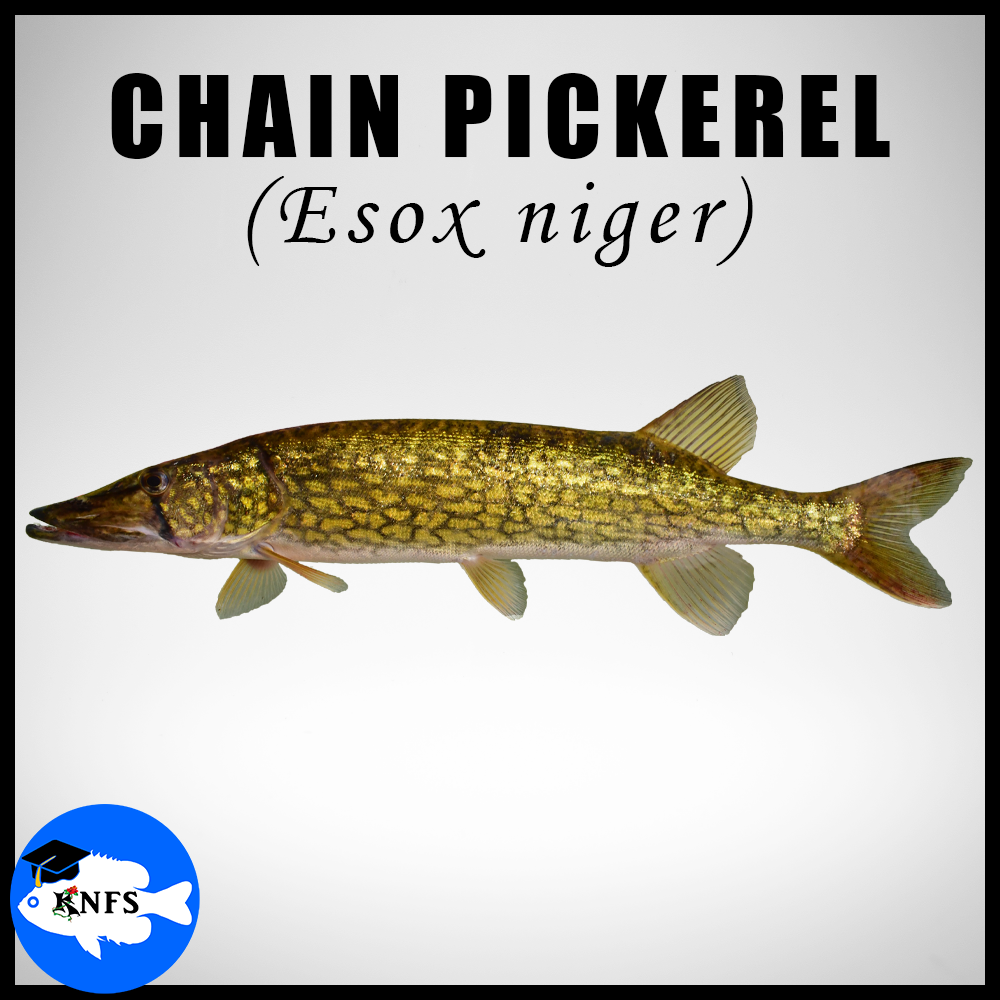

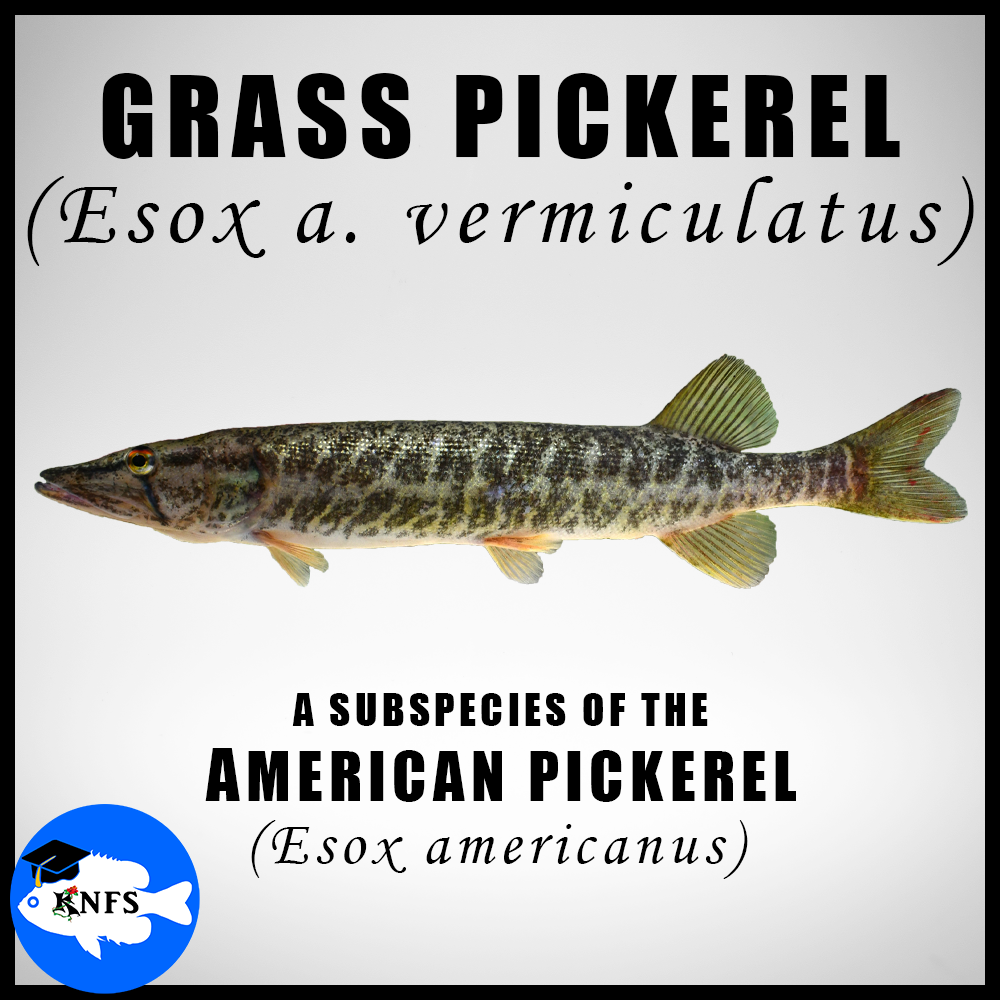

Here in North America, the northern pike is most often confused with chain pickerel (Esox niger) and the muskellunge (Esox masquinongy), and at times, the grass pickerel (Esox americanus vermiculatus). The northern pike may be confused with gars, species from another family of fishes. (See the adjacent graphic to distinguish gars from pikes.)

KEY FEATURE #1 – SCALATION ON CHEEK & OPERCULUM: This trait is the best starting point on any esocid within the genus Esox. However, IDs should never be based solely on this feature. Scalation of the cheek and operculum does vary not just between species but also, to a lesser extent, within species.

Of the North American members of Esox, only the northern pike (E. lucius) and the muskellunge (E. masquinongy) will have an operculum that is only partially scaled, usually appearing half-scaled, give-or-take. The hybrid tiger muskellunge (E. masquinongy x E. lucius) will also show a partially scaled operculum.

The northern pike usually has a fully scaled or mostly fully scaled cheek, similar to the grass, redfin, and chain pickerels (E. a. vermiculatus, E. a. americanus, and E. niger, respectively), while the muskellunge has a cheek that is only partially scaled, though occasionally the cheek may appear up to 80% scaled. The tiger muskellunge will have a cheek that may appear partially scaled or mostly scaled, though usually the latter. [6] [7]

It's important to note that the northern pike’s cheek may appear partially scaled, such as only 80% scaled. Most populations of northern pike will not show a percentage less than 80% on a pure specimen.

The Amur pike (Esox reichertii), though having similar cheek/operculum scalation to the northern pike, is native to the eastern parts of Eurasia. This species, as well as northern pike x Amur pike hybrids, were once stocked in Pennsylvania in the 1970s. This temporary introduction into North American waters prompted Casselmen et al. (1986) to include the Amur pike in their ID guide for North American esocids. [6] [8] [9] However, there is no recent evidence that these populations of Amur pike persisted once the stocking programs halted, ergo the Amur pike is not needed to be addressed further in this guide that only focuses on North American species of Esox.

BODY: Like all members of Esox, the northern pike has an elongated, muscular body built for quick bursts of speed to capture prey. The caudal fin is forked. This forked tail fin is perhaps the easiest feature to compare against the similar looking gars (Lepisosteidae), a completely different group of fishes; all species of gars have rounded caudal fins as well as much larger, diamond-shaped scales.

On the northern pike, a single dorsal fin sits slightly in front of and above an anal fin of similar size. The large ‘duck-bill’-like snout is characteristic of this genus, housing a mouth full of many sharp teeth.

The northern pike usually shows 19-21 anal rays and 21-25 dorsal rays. Other meristic features are discussed below.

KEY FEATURE #2 – SUBMANDIBULAR PORES: Counting the submandibular pores remains one of the best identification features, though this feature should always be considered along with examining other features as some overlap does occur. Only the most obvious pores should be counted. These small pores are hard to examine on juvenile specimens. The pores will be distinct oval-like holes on the underside of the jaw. Take care to avoid counting random flecks and black spots.

Most all northern pike will have a 5/5 count of submandibular pores found on the underside of the jaw, 5 on each side. Though, 4/5 counts are not uncommon and counts of 5/6 do happen. Rarely will the sum of both sides be more than 11 and less than 9 on northern pike.

The muskellunge possesses more submandibular pores than the northern pike, usually with 6 or more submandibular pores on a single side, usually 6-10. The tiger muskellunge (E. masquinongy x E. lucius), the hybrid between the muskellunge and the northern pike, typically shows 9-13 pores combined from each side, usually with counts of 5/5 and with a range of 5/4-7/6, occasionally higher on some specimens. [6] [7]

The grass pickerel, redfin pickerel, and chain pickerel typically show less submandibular pores with counts of 4/4, with 4 pores on each side. Again, counts of 4/5 and 3/4 are not completely uncommon for the pickerels; very rarely 6 pores may show up on a side of any pickerel species. [10]

PATTERNING/COLORATION: Juvenile, subadult, and adult northern pike have very different patterns and coloration.

Adult specimens retain a very distinct ‘jellybean’ like pattern along the body that consists of irregular, elongated ovals of yellowish spotting on a darker olive-green side. The ‘jellybean’ markings may be very circular, or more oval, or even more elongated into small, slanted and wavy bars. At times, adult chain pickerel express very similar patterning to adult northern pike; differentiate chain pickerel from northern pike easiest by examining operculum scalation and submandibular pores.

This ‘jellybean’ patterning on mature northern pike usually continues onto the cheek and operculum, usually with at least a couple of yellowish wavy lines, especially from beneath the eye and into the operculum. The breast and belly are cream to white in color.

Young northern pike, starting at about 2-3 in (6-8 cm) TL, will express a slanting bar pattern along the body, and will not yet start to show the characteristic ‘jellybean’ pattern until ~6 in (15 cm). These slanted light bars are about 1/3 to 1/5 the size of the adjacent dark areas. These 2-3 in (6-8 cm) young northern pike will not express the irregular spotting and blotching in the fins that is characteristic of adults. As the northern pike transitions into the subadult/adult stages, the slanted bars fade, the light spotting pattern develops on the side, and dark spotting begins to show in the fins. Spotting in the fins will usually be apparent by 7 in (18 cm), depending on the population. During this transition, the pigmentation in the fins becomes more apparent, ranging in color from yellow, orange, to red.

Young muskellunge will show spotting in the fins earlier in development than the northern pike, at least as early 3 in (8 cm) for muskellunge, especially in the caudal fin. Muskellunge juveniles show irregular dark spotting on the body, of which, may join together to appear like bars, but remains blotchier and distinctly different than the slanted barring on northern pike juveniles. Muskellunge juveniles also have a more yellow appearances compared to the light green appearance on northern pike.

The ‘silver pike’ is a color morph of the northern pike—not a different species. (No image provided for silver pike.) First recognized by locals in Lake Belletaine of Minnesota, this variant was originally referred to as the ‘silver muskellunge’ until it was verified that this morph is a genetic variant of the northern pike. The silver pike is essentially identical to ‘normal’ northern pike except for distinct superficial characteristics and a few morphometric differences. (Look for the same meristic features as northern pike for identification, i.e., 5/5 submandibular pores, mostly scaled cheek and partially scaled operculum.)

The color of the silver pike is gray to silver with each scale being flecked with gold. The fins are much more finely spotted than typical northern pike. The body is narrower than a typical northern pike, the eyes larger, and the interorbital width is less. Hybrids from silver pike and muskellunge crosses tend to look like normal tiger muskellunge. However, silver pike crossed with normal northern pike tend to have more of a body patterning with dark splotches like a black crappie. The silver pike variant has been found in a number of locations outside Minnesota including Sweden, Manitoba, Ontario, the Northwest Territories, Nebraska, and Alaska. [7] [11] [12]

SMALL BLACK SPOTS? EDIBLE? : Often you will encounter a northern pike that has many small black spots on the outside of the body and even in the meat. These black spots are cysts encasing fluke larvae (flatworms of various species) that are then covered in black pigment. This infection of parasites is called black-spot disease. Northern pike infected with these parasites are suggested to grow slower and suffer higher mortality when infected. [13]

It may seem unappetizing to consume a fish will black-spot disease, however, these fish are edible if cleaned and prepared by cooking. Northern pike also carry broadfish tapeworms (Diphyllobothrium sp.) internally, of which, can cause some unfavorable symptoms for us humans if consumed from a fish not prepared properly. A NOAA funded publication suggests that either normal cooking, smoking to 140 degrees F, or freezing for 48 hours at 0 degrees F will offer safe eating of an infected fish while cold smoking and pickling may not kill these tapeworms. [14]

KEY FEATURE #3 – BRANCHIOSTEGAL RAYS: Counting the branchiostegal rays may be a useful feature to examine, especially on younger specimens that may look like the other esocids—though a magnifying glass may be needed for very small specimens.

Northern pike typically show 13-16 branchiostegal rays on a single side. The muskellunge typically shows 16-20. The grass & redfin pickerels have a lower count, typically between 10-14, rarely up to 15-16. The chain pickerel has much overlap with the northern pike on this feature, usually showing 14-17. The tiger muskellunge, the hybrid between the northern pike and the muskellunge, typically shows 12-20 on a single side.

KEY FEATURE #4 – LATERAL LINE SCALES: For the northern pike, this feature will probably only come in handy if examining juveniles, as mature specimens should be more easily differentiated from other species based off of the easier-to-analyze features above.

Unfortunately, for analyzing purposes, northern pike have a fairly large range of lateral line scales at 105-148, most typically falling between 120-135, usually not more than 145 or less than 115. Muskellunge have more lateral line scales, usually always more than 145 with a range of at least 140-176. So, there is some overlap.

For a faster count, only consider the notched scales in the lateral line. Northern pike typically have between 42-55 notched scales while the muskellunge has 55-77, where again, a small overlap does exist. These notched scales are quite obvious on large specimens, appearing like small horizontal incisions along the lateral line.

The redfin and grass pickerels, in most populations, show less than 110 lateral line scales. Though this range extends from at least 92-117.

Chain pickerel cannot be differentiated confidently from northern pike based off of lateral line scale counts. Of the meristics gathered for this guide, chain pickerel lateral line scales range was 114-138 with only 7% of specimens having fewer than 120 lateral line scales. Casselman et al. (1986) report a chain pickerel lateral line scale range of 114-131. [6] [15] [7] [10] [16]

Click to enlarge.

SIZE: The northern pike, on average, reaches much larger sizes in Eurasia than it does in North America. There are past accountings of found/caught pike reaching 60, 70, 80 and up to 96 pounds, most all in Western Europe, where Ireland seems capable of producing the biggest northern pike. Specimens in North American do not ever seem to surpass 50 pounds. [17]

Max total length of northern pike is ~ 56 in (142 cm). [18] Most adult specimens in North America are between 20-30 in (50-76 cm) TL.

Different water bodies tend to see different size capabilities between populations. The general rule-of-thumb, as it is with muskellunge, is that bigger bodies of water are capable of producing more numbers of the bigger specimens; large bodies of water typically have more abundance of larger prey items, often at deeper depths, able to provide enough food for large pike. Any northern pike bigger than 40 in (101 cm) is considered a very nice-sized catch. A specimen bigger than 32 in (81 cm) is still not too shabby. Certain bodies of water will never be able to produce 40+ in pike.

The IGFA All-Tackle World Record is 55 lb 1 oz (25.0 kg) (from Germany), [19] though, as mentioned above, much larger specimens have been found/caught.

Click to enlarge.

TOOTH LOSS IS WHY SUMMER PIKE DON’T BITE? : Uh…very unlikely. This myth began as a plausible explanation as to why northern pike seem harder to catch during certain periods of the summer. The belief was that pike lost most of their teeth at the same time in the summer and had ‘sore gums’, ergo northerns wouldn’t eat.

However, Trautman and Hubbs studied this curiosity back in the 1930’s and found that tooth loss and tooth regrowth is fairly evenly distributed throughout the year. The northern pike does not lose a large portion of its teeth at the same time at any point during the year. Although tooth loss (and even ‘sore gums’) cannot be completely discredited as a reason as to why a pike might not want to feed, it’s far more likely that the summer-bite drops because of the abundance of natural food items, migrations to deeper depths (where most anglers don’t fish for pike), and/or the general sluggishness that happens to cold-water-fish in warm water. [20]

HABITAT: The northern pike, like all members of the genus Esox, is typically associated with dense vegetation and cover. This cold & cool water species is found in various-sized lakes and rivers, impoundments, backwaters, and pools within creeks. Tall macrophytes, or aquatic plants, often referred to as generic names like “cabbage” and “coontails”, are important habitat types for many stages of northern pike development. These plants are an essential habitat for young pike. Big pike may be found in shallow cabbage, though, an inverse relationship may exist between body size and amount of cover, where too many plants, in some systems, will generally hold an abundance of smaller-sized pike, [21] of which, may be because these densely weeded habitats are unable to produce an abundance of larger prey fish items, a necessary source of food for large pike to exist.

Although most anglers find northerns in water less than 20 ft of depth, larger specimens of this species will also be found at greater depths, especially in deep water lakes that have prey species (like cisco) that are often exclusively found in deeper water. This deep-water habitat often offers a necessary ecological niche for large northern pike to ‘graduate’ into. There are plenty of accounts of anglers netting big pike at depths well over 40’ while targeting smaller fishes. [11]

Northern pike will move throughout the year with the most notable movements being the migrations to-and-from the spawning grounds. This spawning season usually occurs when the ice begins to break along the creeks and rivers that the pike will then transit, often to access marshes or other wetlands, usually starting around February, March, & April depending on the latitude and yearly climate. Once the spawn is complete, the pike return to their summer-through-winter habitat. [22] One study found that northern pike did not set up a normal home range throughout the non-spawn period, but more or less moved randomly about the body of water while preferring to stay near shore and in shallower water. [23]

Click to enlarge. ONLY NORTH AMERICAN RANGE IS SHOWN.

LOCATION: As mentioned earlier, the northern pike is a circumpolar species, found in the northern hemisphere of North America and Eurasia. As this guide is only for North American members of Esox, only the North American range will be discussed.

NATIVE RANGE - The native range of northern pike in North America covers much of Canada and Alaska, extending south into all states of the Great Lakes Basin and farther west through Minnesota, the Dakotas and into the northern parts of Montana. The southernmost part of the natural range extends through central Illinois and central Missouri, though, northern pike in Missouri seem hard to come by these days. [24]

NON-NATIVE RANGE - The range of the northern pike has greatly increased over the last two centuries as stocking events have occurred in many, many locations. Almost every state in the United States has had northern pike at one point in time either from native populations and/or stocking events, both illegal and state-permitted. Not all populations have subsisted from these stocking events, though, many have been successful. Whether these introductions are a benefit or detriment to the local fisheries is another topic in itself. (Not all stocking events are located on the map. Many of the recent and established populations are included.)

The northeastern states of the Atlantic now have well-establish northern pike populations including Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. In Maryland, Deep Creek Lake and the surrounding waters maintain a natural population, as well as the Triadelphia Reservoir and its accompanying drainages. In Virginia, at least a small population exists in Lake Frederick with few other observations of specimens appearing across the state. Over 60 years ago, North Carolina, although attempting to stock northern pike in various locations around the state, did not have success establishing populations.

More places in the Rocky Mountains now contain northern pike populations. This includes more of Montana, eastern parts of Oregon, northern areas in Idaho, and Colorado, mostly in the mountains and along certain places of the Front Range. Texas, New Mexico, Nevada, and Arizona also have scattered populations of northern pike, though most all of Texas’ stocking events didn’t establish. Introduced populations may have persisted in parts of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Georgia.

Arkansas may still have established populations from stockings in Norfolk Reservoir, Beaver Lake, and other locations not seen on the adjacent map.

Although California once stocked northern pike (in the late 1800’s), few sightings have occurred in recent years; Lake Davis in Plumas County may still have northern pike. [25]

FISHING: Worldwide the northern pike is a popular gamefish. This fish reaches exceptional sizes and is capable of giving any angler a fun fight. The meat is usually yellowish in color and can be prepared like any white meat fish. Pike is great to eat and not too strong on the fishy flavor. I’ve probably harvested more northerns than any other species of fish.

There really is so much on the topic of pike fishing that there’s no way it could all be covered here. So, I’ll keep it basic.

FIND WEEDS: Either shallow or deeper submerged vegetation will most likely produce northerns. This species will move around to find favorable water conditions (temperature, dissolved oxygen levels, prey sources, etc.) but they’re still most likely sitting in or around vegetation. (That’s not to say pike don’t go deep, especially those big pike in lakes with deep-water prey where pike may be foraging around 40’ depth. (It’s very tricky to catch suspending pike at depth.)

FIND ONE, FIND MORE: If you happen upon a northern pike in a section of water, then keep fishing that area. It’s common to find a group of northerns in a small 20’ x 20’ area of water.

This omnivorous species is primarily piscivorous (eats fish) especially in the adult stage of life but is truly an opportunistic feeder, as in, it’ll eat just about any creature that’ll fit in its mouth. Fish-mimic baits are great. It’s probably harder to find a bait that won’t work for northern pike than finding one that will. Northern pike will even eat dead food items—so a lifeless minnow is still a great bait option for a northern.

GREAT BAIT OPTIONS:

LIVE BAIT: A large live minnow or other baitfish will definitely attract a northern. (A quick-strike rig is recommended on large baitfish, especially if fishing in waters with musky. It’s safer for the pike/musky.) Pike will target very large prey items compared to their own body size. Typically, you want a baitfish that is about 1/3 in size of the pike that you want to target. If targeting 30” pike then go with the 9-10” baitfish. Though, purchasing a bunch of 9-10” baitfish can empty pockets quickly. A 30” pike will still gladly snack on a 4-5” baitfish.

SAFETY-PIN SPINNERBAITS: I cannot enumerate the number of northerns I’ve landed on safety-pin spinnerbaits. This lure type is mostly weedless, has more than enough flash and thump, and these spinnerbaits can be played at almost any depth. Likewise, you can’t go wrong with an in-line spinnerbait. Though, in-line spinners are typically with treble hooks and will need to be played on the very top of the weeds.

PICK A HARDBAIT…ANY HARDBAIT: Topwater baits in lily pads and over cabbage beds will do great. Jerkbaits over cabbage and along weed edges will also have success. Depth targeting crankbaits will do well to take stabs at those deep-water targets.

Fast and hard retrievals will produce plenty of reaction strikes. Spoons in open water are also popular pike lures. The northern pike is not picky—this species is very impulsive, unlike its cousin, the muskellunge, a fish that is notorious for making anglers put in the hours.

Fish responsibly and good luck!

REFERENCES:

[1] C. Linnaeus, "Systema Naturae, Ed. X.," vol. 1, no. i-ii, p. 1758.

[2] R. Fricke, W. N. Eschmeyer and R. van der Laan, "ESCHMEYER'S CATALOG OF FISHES: GENERA, SPECIES, REFERENCES".

[3] P. G. Bianco and G. B. Delmastro, "Recenti novità tassonomiche riguardanti i pesci d'acqua dolce autoctoni in Italiae e descrizione di una nuova specie di luccio.," Researches on Wildlife Conservation, vol. 2, pp. 1-13, 2011.

[4] L. Lucentini, M. E. Puletti, C. Ricciolini, L. Gigliarelli, D. Fontaneto, L. Lanfaloni, F. Bilo, M. Natali and F. Panara, "Molecular and phenotypic evidence of a new species of genus Esox (Esocidae, Esociformes, Actinopterygii): the southern pike, Esox flaviae.," PLoS ONE, vol. 6, no. 12, pp. 1-14, 2011.

[5] G. P. J. Denys, A. Dettai, H. Persat, M. Hautecoeur and P. Keith, "Morphological and molecular evidence of three species of pikes Esox spp. (Actinopterygii, Esocidae) in France, including the description of a new species.," Comptes Rendus Biologies, vol. 337, pp. 521-534, 2014.

[6] J. M. Casselman, E. J. Crossman, P. E. Ihssen, J. D. Reist and H. E. Booke, "Identification of Muskellunge, Northern Pike, and their Hybrids," Am. Fish. Soc. Spec. Publ., vol. 15, pp. 14-46, 1986.

[7] S. Eddy, "Hybridization between Northern Pike (Esox lucius) and Muskellunge (Esox masquinongy)," Jour. of the Minn. Acad. of Sci., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 38-43, 1944.

[8] D. R. Graff and L. R. Sorenson, "The Successful Feeding of a Dry Diet to Esocids," The Progressive Fish-Culturist, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 31-35, 2011.

[9] E. J. Crossman and J. W. Meade, "Artificial hybrids bewteen Amur pike, Esox reichertii, and North American esocids," Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, vol. 34, pp. 2338-2343, 1977.

[10] E. J. Crossman, "A Taxonomic Study of Esox americanus and Its Subspecies in Eastern North America," Copeia, vol. 1, pp. 1-20, 1966

[11] A.J. McLane, McClane's New Standard Fishing Encyclopedia, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1974.

[12] E. Crossman and K. Buss, "Hybridization in the Family Esocidae," J. Fish. Res. Bd., vol. 22, no. 5, 1964.

[13] E. J. Harrison and W. F. Hadley, "Possible Effects of Black-Spot Disease on Northern Pike," Trans. of the Am. Fish. Soc., vol. 111, pp. 106-109, 1982.

[14] J. Gunderson and N. Berini, "PARASITES: ARE THE FISH GOOD ENOUGH TO EAT?," Minnesota Sea Grant -NOAA, 1982.

[15] Koaw, "Select Morphometrics and Meristics of Esocids," Koaw Nature - KNFS, 2023.

[16] E. J. Crossman, "The Redfin Pickerel, Esox a. americanus in North Carolina," Copeia, vol. 1962, no. 1, pp. 114-123, 1962.

[17] A. Lindner, F. Buller, D. Stange, D. Csanda, R. Lindner, B. Ripley and J. Eggers, Northern Pike Secrets, In-Fisherman.

[18] L. M. Page and B. M. Burr, Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of North America North of Mexico, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011.

[19] IGFA - The International Game Fish Association, "Esox lucius World Record," IGFA.

[20] M. B. Trautman and C. L. Hubbs, "When do Pike Shed their Teeth?," Trans. of the Amer. Fish. Soc., vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 261-266, 1935.

[21] J. M. Casselman and C. A. Lewis, "Habitat requirements of northern pike (Esox lucius)," Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, vol. 53, pp. 161-174, 1996.

[22] A. Bosworth and J. M. Farrell, "Genetic Divergence among Northern Pike from Spawning Locations in the Upper St. Lawrence River," North American Journal of Fisheries Management, vol. 26, pp. 676--684, 2006.

[23] J. S. Diana, W. C. Mackay and M. Ehrman, "Movements and Habitat Preference of Northern Pike (Esox lucius) in Lac Ste. Anne, Alberta," Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, vol. 106, no. 6, pp. 560-565, 1977.

[24] E. J. Crossman, "Taxonomy and Distribution of North American Esocids," American Fisheries Society Special Publication, no. 11, pp. 13-26, 1978.

[25] USGS-NAS, "Esox lucius - Northern Pike Point Map," USGS NAS - Nonindigenous Aquatic Species.

[26] D. B. McCarraher, "Extension of the Range of Northern Pike (Esox lucius)," Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, vol. 90, no. 2, pp. 227-228, 1961.

[27] E. H. Brown and C. F. Clark, "Length—Weight Relationship of Northern Pike, Esox lucius, from East Harbor, Ohio," Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, vol. 94, no. 4, pp. 404-405, 1965.

[28] D. B. McCarraher, "Northern Pike, Esox lucius, in Alkaline Lakes of Nebraska," Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, vol. 91, no. 3, pp. 326-329, 1962.