A visit from an executioner changed Joel Dimsdale's life.

This was in the 1970s. Dimsdale, a psychiatrist, had recently published a paper about his research on Holocaust survivors. He was working in his office in Massachusetts General Hospital, when he heard a pounding on his door, as he recalls.

"I open the door and there's a man I didn't know carrying a gun case," Dimsdale says. "And he says: 'I'm the executioner and I've come for you.'"

"With that he sat down on my couch and started opening up the gun case and I said a little prayer to myself and wondered who I had infuriated so much," Dimsdale recalls.

But the visit wasn't murderous. Instead, the stranger pulled papers out of his case to prove that he was Joseph Malta, one of two executioners who had put to death Nazi criminals at Nuremberg's Landsberg Prison, in 1946.

"It was a pleasure doing it," Malta told the Associated Press in 1996, three years before his death. "I'd do it all over again," he added.

Still, in the 70s, Malta told Dimsdale that he wondered how these men could commit such terrible acts. He urged the psychiatrist to expand his study to include the perpetrators, as well as the victims. Although he couldn't very well summon up dead men, Dimsdale took an interest, and did the next best thing: he dug into the historical record. It turns out that two prominent American researchers conducted a battery of psychological tests on Nazi war criminals during the Nuremberg trials.

Dimsdale's studies led to a 1980 book entitled Survivors, Victims and Perpetrators: Essays on the Nazi Holocaust, as well as subsequent research. Earlier this year, he published a study in the Journal of Psychosomatic Research covering one of the largely-forgotten tests administered to the Nazis: Rorschach inkblot tests.

Dimsdale explains that while the Nazis were imprisoned, American psychiatrist Douglas Kelley and psychologist Gustave Gilber administered Rorschach tests to many of them. The men soon clashed, however, in part due to their different backgrounds: Kelley was a gifted psychiatrist and polymath who was an expert in evaluating Rorschach tests, but he didn't speak German and had to communicate through a translator. Gilbert, on the other hand, was fluent in German but knew little about the test.

Mainly, though, they began to differ over interpretations of the nature of the Nazis, and of evil deeds in general. Gilbert came to the conclusion that the men were "demonic psychopaths," whereas Kelley's view was that "war criminal behavior exists on a continuum, and it's likely that many people would stoop to such behavior in certain circumstances," Dimsdale says.

The effort to study these Nazis "constituted a heroic effort on the part of researchers to try to understand the psychopathology of mass killers," he says. "Never before have you had [members of] the leading cabinet of a country on trial…and had the will or opportunity to study them."

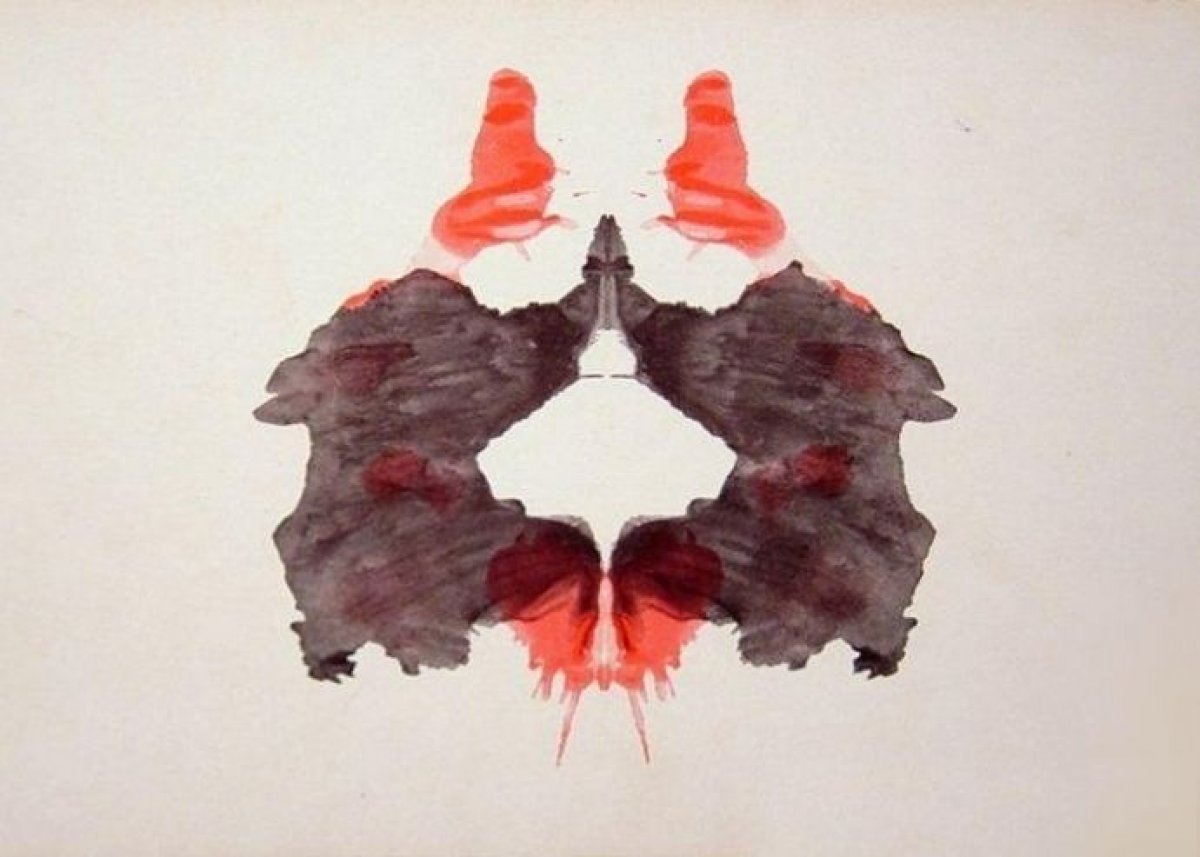

Rorschach tests, en vogue at the time (but now little-used, due to the perception among many that their results are prone to biased assessment and difficult to reliably quantify), consist of different-colored blots of ink in various vague shapes. These are presented to patients, who are asked to interpret what the inky figures mean. Many psychologists thought at the time that by analyzing enough healthy people's interpretations of the images, they could get an idea of what "normal" responses were, so anything that diverged would stand out as unusual. Themes that emerged from an individual patient's analysis could also speak to the person's personality and, perhaps, the life of his or her unconscious mind. Some experts thought the test could help reveal certain mental and thought disorders.

Kelley and Gilbert spent many hours administering the tests to the likes of Hermann Goering (widely considered one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany, and Hitler's likely successor), Robert Ley (head of the German Labor Front), Rudolf Hess (Deputy Fuhrer), Julius Streicher (an early prominent Nazi who was so violent even his fellow party members had him stripped of his power, Dimsdale says), and others.

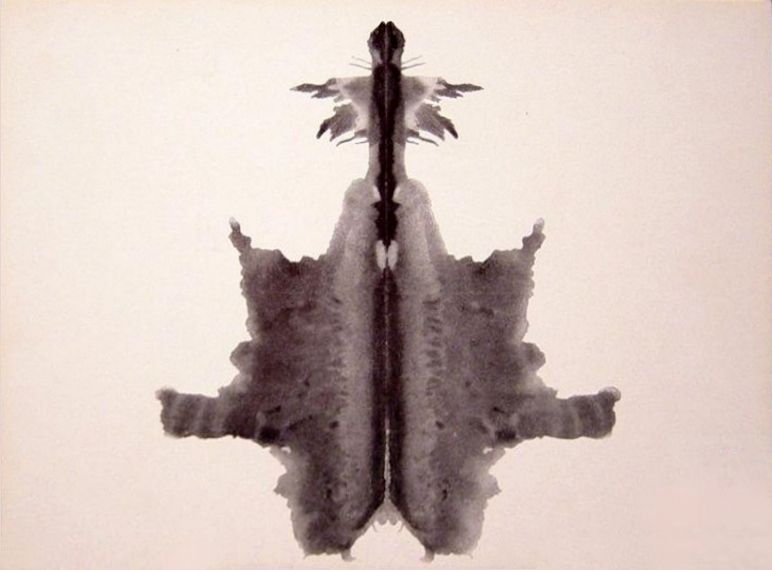

Responses to the second of ten cards used in the Rorschach test (seen above) shed some interesting light on the Nazis examined, but also reveal the limitations of such an evaluation. Goering, also the founder of the Gestapo and Commander in Chief of the Luftwaffe, responded thus when asked what he saw in the card: "Two dancing men. A fantastic dance. Two men, here are their heads, their hands together, like whirling dervishes. Here are their bodies, their feet."

This card and response were later analyzed by psychologists Florence Miale and Richard Selzer, who wrote that Goering's interpretation of seeing "two dancing figure" reflected a "hypomanic defense," which can be a symptom of a bipolar spectrum disorder. Miale and Selzer believed that Goering's vision of two faces, one in both the black ink blot and the white space, "strongly suggests the emptiness of his being" and that when he reported the hat as red, it "indicates an emotional preoccupation with status."

Certainly Goering was slick and charming, a "chameleon in terms of shaping his behavior based on audience. He could be warm and charming, or brutal," Dimsdale says.

Ley, on the other hand, reported seeing "the jaws of a butterfly," and gave other unsettling responses. He was known to have had a history of head injuries, and for his impulsivity and alcoholism.

Meanwhile, Julius Streicher "seemed fixated on leitmotifs of revolution," Dimsdale writes. When shown the card, Streicher stated definitively that the ink blot represented "two women in the French Revolutionary times with Jacobean caps." Rudolf Hess, who flew solo to Scotland in 1941 and was captured by the allies, reported seeing a "microscopic cross section; parts of an insect with blood spots; a mask." This interpretation is quite unusual and points to an underlying thought disorder, says Thomas Wise, a professor psychiatry at Virginia Commonwealth University who wasn't involved in the paper.

Miale and Selzer viewed his responses as "the remnants of a violent, excitable, unrelated emotionality, which is still intense but is split off from contact with anything real."

Dimsdale writes that there are two main problems with interpreting the results. After thousands of sessions, one can get an idea of what a common or uncommon response is. But context is key. "Who knows what is a strange response in a jailed cabinet minister facing a death sentence?" Dimsdale says. Secondly, bias plays a huge role. "If you knew the inkblot record came from a Nazi war criminal, could you possibly interpret it dispassionately?"

To the extent that the tests tell us more about the Nazi's personalities, they are useful, Dimsdale say. But it can't all be explained scientifically. "They were mostly not psychotic by our normal definitions—though Streicher probably was." Mainly, they were "fundamentally bad guys, but that's not a psychiatric diagnosis," Wise says.

Dimsdale tends to see more eye-to-eye with Kelley in his analysis of the Nazis. Despite the fact that people are tempted to view with as "demonic monsters, Frankenstein-like," he says, "many of the Nazi leaders were careerists, bureaucrats, desk murderers who went home, petted their dog, had dinner with their families, and returned to do unspeakable things the next morning at work.

"I believe that these studies of war criminals are useful in allowing people to recognize the sad panoply of malice that's out there," Dimsdale says. "If we have childish ideas that all bad guys are all one flavor, we're going to be sorely misguided if we're going to recognize our own evils in the future."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Douglas Main is a journalist who lives in New York City and whose writing has appeared in the New York ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.