James Cadariu was born and bred in a neighbourhood that’s now falling to pieces. In the late 1980s, Cadariu’s mother and brother were held up at gunpoint in the east side of Detroit. They fled for the suburbs, part of the massive “white flight” that helped turn Detroit from a bustling city of two million into a city of under 700,000. Those who stuck it out became unwilling icons of the supposed decline of the American empire, the subject of a thousand news articles, documentaries and books.

Cadariu, now 44, was sick of seeing his city like that. So he came back. He now co-owns Great Lakes Coffee Roasting Company, which has a retail outlet on Woodward Ave in Midtown and sells fairtrade coffee for about $4 a cup. It sits across from a Whole Foods, down the street from a craft brewery and right along the M-1, a new streetcar line that will connect midtown with downtown – two neighbourhoods that have seen their fortunes rise as Detroit emerges from bankruptcy and attracts new businesses, infrastructure and residents at rates not seen in decades.

“I’ve seen Detroit as a large city. I’ve seen it decline,” Cadariu said. “But I’ve never seen as much growth downtown as I do now. A lot of times we get crap because there are a bunch of white hipsters opening businesses, but we have the same vision: seeing people back here.”

And then there’s the rest of Detroit. In the neighbourhoods outside the downtown core, residents earn an average of 25% less. Housing is crumbling. There are 150,000 vacant or abandoned buildings. In some areas, just one or two houses keep entire blocks from reverting to grassland.

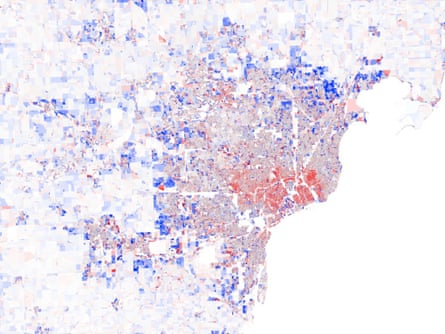

Boomtown and icon of ruinous decline – to say these two Detroits co-exist would be too optimistic. Separated by as little as a city block, the new Detroit and the rest of Detroit feel like two completely different cities – physically close, far apart in everything else: education, income, outlook on their future. The recent news that a racial blockade was erected between a predominantly black outer neighbourhood and the more opulent white suburb of Grosse Point is disturbing but somehow not surprising. Detroiters may hate being a symbol for the US, but in this way they really are: where there’s been a confluence of public incentives and private investment, Detroit – like Manhattan and north Brooklyn – is booming. In the rest of Detroit – like in the rest of New York – the chasm between rich and poor is growing.

But what makes Detroit unique is the insistence that these pockets of wealth (and whiteness) will somehow rescue the city. Economic czar George Jackson put it plainly when he said of gentrification: “Bring it on.”

And so the city has. Dan Gilbert, the billionaire owner of Quicken Loans, bought more than 60 buildings in downtown Detroit and gets called everything from a missionary to a superhero – despite the fact that his company has been accused of aggressive sales practices. Mike Ilitch, owner of Little Caesars Pizza and two Detroit sports teams, has similarly bought up real estate on the cheap. These billionaires of Detroit, along with the leaders of the car companies and the nonprofits they fund, have used their influence to build billions of dollars’ worth of infrastructure. Detroit is 138.7 square miles, larger than Boston, San Francisco and Manhattan combined, but the vast majority of the new money that has poured into the city has pooled in the 7.2 square miles of downtown.

The riverfront has become a particular magnet. The non-profit Detroit Riverfront Conservancy has convinced landowners to grant permanent easements for it to build a 5.5 mile walkable, bikeable strip along the water’s edge. The Conservancy also helped plan and fund the Dequindre Cut, a bike path on a former rail line that connects the river to Eastern Market, one of the largest farmers’ markets in the US. There’s also the M-1 Rail, pitched as a commuter rail that would eventually stretch into Detroit’s northern suburbs, but since whittled down to a 3.3-mile streetcar that for now connects only downtown and Midtown.

The infrastructure has spurred a real estate boom. Vacancy rates in the core are mostly under 5%, and about $2bn of real estate was constructed or planned between 2010-12, according to a report. Downtown rents are $200-400 higher than a year ago and approaching $2/sq ft, the “magic number” developers see as the threshold for new construction being profitable. Tech startups are plentiful. Artists are being lured by cheap rent. Small manufacturers are moving in, and big companies are offering incentives for their young employees to live in the city centre.

Developers argue that it’s just a matter of time before other neighbourhoods rise up, too. “Folks want to move from zero to investable project, and it just doesn’t work that way,” said David Blaszkiewicz, the president of Invest Detroit, a development company that works with nonprofits and corporations to funnel money into the city core. “You start with the best neighborhoods and you migrate to the most challenged neighborhoods.”

There’s not a lot of evidence that this kind of trickle-down economics works. In New York, for example, even as average rents rise beyond $3,800 in Manhattan, nearly half the city’s residents live near the poverty line.

Jocelyn Harris has lived in one of those “challenged” outer Detroit neighborhoods, about six miles east of downtown, all her life. Her house is one of the only occupied properties on her block. Almost everyone else has moved away. She fears that if the city doesn’t help soon, she might be the only resident left. Instead, she says, the city frequently locks the local park gates even when they’re supposed to be open. When a nearby school closed, Harris and some neighbours proposed turning it into a community centre. The city sold it to a private developer – a sign to outer-neighbourhood residents of the city’s lack of regard for their needs.

“We used to have everything: department stores, grocery stores, all of it,” Harris said. “Now the sewage backs up, the park is locked, the school is closed. If we only had more repair dollars, people could have stayed here. It’s been a lot of fighting just to keep it like this.”

Part of the knock-on impact is that residents of these under-serviced areas aren’t ready to take advantage of jobs coming to the city. Residents of Detroit’s outer neighbourhoods are not only poorer and worse-prepared for jobs than those in the core, where the per capita income of the 36,000 residents is more than $5,000 higher ($20,200) than the city as a whole, but young people are about four times less likely to be college educated.

The state’s work training programme, Michigan Works, is meant to help unskilled residents take advantage of the construction boom, but applicants have to pass a test that includes maths and reading comprehension first – and “people don’t know enough about algebra,” said Michael Christopher, a resident of Delray, one of the city’s poorest and most neglected neighbourhoods. “Are we getting the people of Detroit, the people of Delray, ready for these new jobs?”

The city is not blind to the problem. It has begun an aggressive blight-removal effort in targeted neighbourhoods like Harris’s and has installed high-powered street lights in about 80% of the outer districts. Residents say they hope these are the first sign that things are about to change for the better – that sometime, eventually, their communities will come back to life like downtown and midtown. But for now there’s little that outer Detroit’s residents can do to benefit from the boom.

“If we could get the services back, people will come back,” said Jessica Howell, Harris’ sister. “Our goal and our prayer is that Detroit will not only come back, but come back better.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion