Congo Killies - PageSuite

Congo Killies - PageSuite

Congo Killies - PageSuite

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

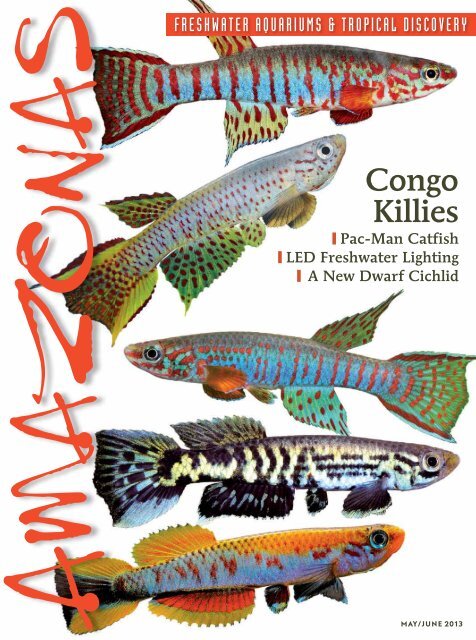

FRESHWATER AQUARIUMS & TROPICAL DISCOVERY<br />

<strong>Congo</strong><br />

<strong>Killies</strong><br />

❙ Pac-Man Catfish<br />

❙ LED Freshwater Lighting<br />

❙ A New Dwarf Cichlid<br />

MAY/JUNE 2013

EDITOR & PUBLISHER | James M. Lawrence<br />

INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHER | Matthias Schmidt<br />

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF | Hans-Georg Evers<br />

CHIEF DESIGNER | Nick Nadolny<br />

SENIOR ADVISORY BOARD |<br />

Dr. Gerald Allen, Christopher Brightwell, Svein A.<br />

Fosså, Raymond Lucas, Dr. Paul Loiselle, Dr. John<br />

E. Randall, Julian Sprung, Jeffrey A. Turner<br />

SENIOR EDITORS |<br />

Matthew Pedersen, Mary E. Sweeney<br />

CONTRIBUTORS |<br />

Juan Miguel Artigas Azas, Dick Au, Heiko Bleher,<br />

Eric Bodrock, Jeffrey Christian, Morrell Devlin,<br />

Ian Fuller, Jay Hemdal, Neil Hepworth, Maike<br />

Wilstermann-Hildebrand, Ted Judy, Ad Konings,<br />

Marco Tulio C. Lacerda, Michael Lo, Neale Monks,<br />

Rachel O’Leary, Martin Thaler Morte, Christian &<br />

Marie-Paulette Piednoir, Karen Randall, Mark<br />

Sabaj Perez, Ph.D., Ben Tan<br />

TRANSLATOR | Stephan M. Tanner, Ph.D.<br />

ART DIRECTOR | Linda Provost<br />

DESIGNER | Anne Linton Elston<br />

ASSOCIATE EDITORS |<br />

Louise Watson, John Sweeney, Eamonn Sweeney<br />

EDITORIAL & BUSINESS OFFICES |<br />

Reef to Rainforest Media, LLC<br />

140 Webster Road | PO Box 490<br />

Shelburne, VT 05482<br />

Tel: 802.985.9977 | Fax: 802.497.0768<br />

BUSINESS & MARKETING DIRECTOR |<br />

Judith Billard | 802.985.9977 Ext. 3<br />

ADVERTISING SALES |<br />

James Lawrence | 802.985.9977 Ext. 7<br />

james.lawrence@reef2rainforest.com<br />

ACCOUNTS | Linda Bursell<br />

NEWSSTAND | Howard White & Associates<br />

PRINTING | Dartmouth Printing | Hanover, NH<br />

CUSTOMER SERVICE |<br />

service@amazonascustomerservice.com<br />

570.567.0424<br />

SUBSCRIPTIONS | www.amazonasmagazine.com<br />

WEB CONTENT | www.reef2rainforest.com<br />

AMAZONAS, Freshwater Aquariums & Tropical Discovery<br />

is published bimonthly in December, February, April,<br />

June, August, and October by Reef to Rainforest Media,<br />

LLC, 140 Webster Road, PO Box 490, Shelburne, VT<br />

05482. Application to mail at periodicals prices pending at<br />

Shelburne, VT and additional mailing offices. Subscription<br />

rates: U.S. $29 for one year. Canada, $41 for one year.<br />

Outside U.S. and Canada, $49 for one year.<br />

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: AMAZONAS,<br />

PO Box 361, Williamsport, PA 17703-0361<br />

ISSN 2166-3106 (Print) | ISSN 2166-3122 (Digital)<br />

AMAZONAS is a licensed edition of<br />

AMAZONAS Germany, Natur und Tier Verlag GmbH,<br />

Muenster, Germany.<br />

All rights reserved. Reproduction of any material from this<br />

issue in whole or in part is strictly prohibited.<br />

COVER:<br />

Various Aphyosemion species.<br />

Images by Olaf Deters.<br />

4 EDITORIAL by Hans-Georg Evers<br />

6 AQUATIC NOTEBOOK<br />

FEATURE ARTICLES<br />

22 APHYOSEMION IN THE CONGO BASIN<br />

by Jouke van der Zee and Rainer Sonnenberg<br />

34 THE KEEPING OF APHYOSEMION IN THE AQUARIUM<br />

by Olaf Deters<br />

40 BREEDING APHYOSEMION<br />

by Olaf Deters and Michael Schlüter<br />

48 AQUATIC TRAVEL:<br />

In search of the Blue-eyed Plec<br />

by Heiko Bleher<br />

54 HUSBANDRY & BREEDING:<br />

A native jewel: Etheostoma caeruleum,<br />

the Rainbow Darter<br />

by Ken Zeedyk<br />

62 HUSBANDRY AND BREEDING:<br />

Triops: Tadpole shrimp in the aquarium<br />

by Timm Adam<br />

68 AQUATIC PLANTS:<br />

Shedding new light on a planted aquarium<br />

by Thomas Hörning<br />

74 HUSBANDRY AND BREEDING:<br />

Breeding success with the Pac-Man catfish,<br />

Lophiosilurus alexandri<br />

by Ivan Chang<br />

80 HUSBANDRY AND BREEDING:<br />

Using a trick to rear Apistogramma playayacu<br />

by Hans Georg-Evers<br />

84 HUSBANDRY AND BREEDING:<br />

Ancistrus claro: a dwarf among the L-number catfishes<br />

by Jörn Sabisch<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

86 AQUARIUM CALENDAR:<br />

Upcoming events<br />

by Mary E. Sweeney<br />

88 RETAIL SOURCES<br />

90 SPECIES SNAPSHOTS<br />

94 SOCIETY CONNECTIONS<br />

97 ADVERTISER INDEX<br />

98 UNDERWATER EYE<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

3

EDITORIAL<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

Dear Reader,<br />

Fishes from Africa play almost no role in the modern<br />

aquarium trade today, unless they come from the<br />

famous Rift Lakes. This, of course, was not always the<br />

case. During my youth, the cichlids and the small<br />

but very vibrant killifishes of Central and West Africa<br />

were quite popular.<br />

Killifishes were kept then—as they<br />

are now—mostly by specialists, but they<br />

were more commonly mentioned in the<br />

literature and more often seen at shows<br />

and auctions. Today, killifish enthusiasts<br />

appear to operate much more under the<br />

radar. However, our knowledge about<br />

these colorful dwarfs is vast, and scientists<br />

and amateur enthusiasts have contributed<br />

much to it in recent years.<br />

One of our editorial board members,<br />

Olaf Deters, is very active in this sphere of<br />

interest, so it was just a matter of time before<br />

we chose killifishes as a cover theme.<br />

We have intentionally focused on the genus<br />

Aphyosemion because the name is well<br />

recognized and there are many new and<br />

exciting insights to tell you about. An African cover<br />

story is quite unusual for us, but I hope you enjoy this<br />

peek beyond the usual horizon.<br />

When water plant enthusiasts gather, the question<br />

of lighting will almost always come up sooner or<br />

later. We have wanted to report on this topic for some<br />

time, and in this issue we include hands-on articles<br />

on the ever more popular LEDs. In the marine hobby,<br />

this technology is already widespread and fast becoming<br />

an accepted technology.<br />

For a catfish buff like me, the breeding report on<br />

the Pac-man Catfish, Lophiosilurus alexandri, is truly<br />

a highlight. Similarly exciting is the story about the<br />

Blue-Eyed Pleco, which is certain to start a lively discussion—and<br />

not just among catfish followers.<br />

When I look over this new issue, with its many<br />

interesting stories that should excite a diversity of true<br />

addicts, I cannot stop grinning! It is amazing what<br />

both hobbyists and scientists have to report. Quite<br />

the opposite of predictable, fishkeeping is far better<br />

than reality television for most of us. I would much<br />

rather spend my time in the fish room than turn into<br />

a dazed sofa spud.<br />

Enjoy the issue, and happy fishkeeping!<br />

4

Only POLY-FILTER®and KOLD STER-IL®filtration provides superior water<br />

quality for optimal fish & invertebrate health and long-term growth.<br />

POLY-FILTER® — the only chemical filtration medium that actually<br />

changes color. Each different color shows contaminates, pollutants<br />

being adsorbed & absorbed. Fresh, brackish, marine and reef inhabitants<br />

are fully protected from: low pH fluctuations, VOCs, heavy metals,<br />

organic wastes, phosphates, pesticides and other toxins. POLY-FILTER®is<br />

fully stabilized — it can’t sorb trace elements, calcium, magnesium,<br />

strontium, barium, carbonates, bicarbonates or hydroxides.<br />

Use KOLD STER-IL®to purify your tap water. Zero waste! Exceeds US EPA & US<br />

FDA standards for potable water. Perfect for aquatic pets, herps, dogs,<br />

cats, plants and makes fantastic drinking water. Go green and save!<br />

117 Neverslnk St. (Lorane)<br />

Reading, PA 19606-3732<br />

Phone 610-404-1400<br />

Fax 610-404-1487<br />

www.poly-bio-marine.com<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

5

AQUATIC<br />

NOTEBOOK<br />

article and images by Ralf Britz<br />

Three new fish species from Southern India<br />

The fish fauna of the so-called Western Ghats, a mountain range that extends parallel to the<br />

west coast of India over a distance of 1,600 km (1,000 mi.) from Maharashtra in the north to<br />

Kerala in the south, is considered one of the best-studied ichthyofaunas in this country. Sykes<br />

(1839) and Jerdon (1849) published the first monographs of the freshwater fish fauna, which<br />

were followed by those of Day and Hora and their co-workers. A recent compilation by the<br />

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listed 290 different species of fishes<br />

(Dahanukar et al. 2011). The best-known species of the Western Ghats is the Red-Line Torpedo<br />

Right: Type<br />

locality of Pangio<br />

ammophila<br />

Below:<br />

Pangio ammophila<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

6

Pristolepis<br />

rubripinnis<br />

Barb, Puntius denisonii. Other popular species found<br />

there include Carinotetraodon travancoricus and Pristolepis<br />

marginata. While on a short collection trip with Indian<br />

colleagues in different river systems in Karnataka and<br />

Kerala, we were able to collect several new fish species,<br />

which we have described in the past few months. A big<br />

surprise for us was the discovery of a second Indian Pristolepis<br />

species, P. rubripinnis, which differs significantly<br />

from the known species P. marginata. We were able to<br />

capture a number of specimens of this fish, which has<br />

beautiful orange fin fringes, at night in the Pamba River.<br />

We hope that this species will soon be imported, because<br />

it is a very pretty fish.<br />

In some recently published Indian publications, a<br />

second Pristolepis species, P. fasciata, was mentioned;<br />

however, this species is native to Indonesia. Whether the<br />

fish called P. fasciata in the Indian literature is potentially<br />

identical to P. rubripinnis could not be clarified due to the<br />

lack of reference specimens.<br />

A second unexpected freshwater fish was caught in<br />

a tributary of the Barapole River in southern Karnataka.<br />

This exciting new Badidae was co-discovered by the Indian<br />

aquarium fish lover Nikhil Sood from Bangalore and<br />

his German friend Benjamin Harink. Harink reported<br />

about it on the forum of the IGL (International Society<br />

for Labyrinth Fishes). Sood took us to the location and<br />

we were able to capture a number of these chameleonfishes<br />

in a few hours. The river was up to 10 meters (33<br />

feet) wide and 2 meters (6.5 feet) deep. Large stands of<br />

aquatic plants such as Blyxa, Lagenandra, and Cryptocoryne<br />

were present. The new species was hidden, mainly<br />

in leaf litter that had accumulated in the shallower areas,<br />

and could be shaken out of the roots along the riverbank.<br />

During our research to describe the species, we<br />

discovered that Francis Day, one of the fathers of<br />

Indian ichthyology, had already collected this fish, but<br />

he believed it belonged to the taxon Dario dario. There<br />

were also some specimens collected by Day, said to be<br />

from “Wynaad,” in the collection of the Natural History<br />

Museum in London, which, together with the newly<br />

collected animals, served as the basis for the description.<br />

For completeness, it should be mentioned that in June<br />

2010, a group of Indian aquarists caught the same (or a<br />

very similar-looking) species in the Sita River, part of the<br />

Kaveri River system. Rahul Kumar pointed that out to me<br />

on the Indianaquariumhobbyist.com forum.<br />

Interestingly, the new Dario shows some features<br />

usually found in Badis species, such as the striking caudal<br />

peduncle spot, which has led to the species name Urops.<br />

This trait, however, is an ancestral trait and of no use in<br />

determining the relationship. The total absence of the<br />

lateral line, various lateral line pores in the head region,<br />

and the lack of gill rakers on different gill arches clearly<br />

place the species D. urops in the genus Dario, since these<br />

are all derived features.<br />

Compared to other Badidae species, Dario urops is<br />

not exactly the most colorful of species, but it will surely<br />

fascinate fans of chameleonfishes. It remains to be documented<br />

how Dario urops propagates—like Badis species,<br />

via parental care by the male in a nest, or as egg scatterers<br />

in dense vegetation without parental care, like other<br />

Dario species. Aquarists still can contribute meaningfully<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

7

Type locality of Dario urops<br />

Male of Dario urops<br />

TM<br />

in this respect. Nikhil Sood maintained these animals successfully for several<br />

months in a cool aquarium with faintly moving neutral and soft water, a<br />

sandy bottom, and a lot of leaf litter.<br />

The third new species from the Western Ghats that we found in our nets<br />

was a new Pangio. We named it Pangio ammophila because of its lifestyle. The<br />

handful of specimens of this small, scaleless Pangio that we captured were<br />

buried in the sand of the Kumaradhara River. Because of its plain appearance<br />

it is unlikely that it will make it into the aquarium fish trade.<br />

Another very unusual Pangio species has been described from the Western<br />

Ghats. Pangio goaensis is known not only from Goa but also from several rivers<br />

in Kerala, in the south. This Pangio is spectacularly striped; apparently, no<br />

pictures of live specimens were taken.<br />

Our small-scale collecting trip to southern India has shown that this supposedly<br />

well-known part of India still holds many surprises, and with a little<br />

luck, a few of them might make it into the hobby.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

Britz, R., A. Ali, and R. Raghavan. 2012. Pangio ammophila, a new species of eel-loach from<br />

Karnataka, southern India (Teleostei: Cypriniformes: Cobitidae). Ichthyol Explor Freshwaters 23:<br />

45–50.<br />

Britz, R., A. Ali, and S. Philip. 2012. Dario urops, a new species of badid fish from the Western Ghats,<br />

southern India (Teleostei: Percomorpha: Badidae). Zootaxa 3348: 63–68.<br />

Britz, R., K. Kumar, and F. Baby. 2012. Pristolepis rubripinnis, a new species of fish from southern India<br />

(Teleostei: Percomorpha: Pristolepididae). Zootaxa 3345: 59–68.<br />

8

Advanced aquarists choose from a proven leader in<br />

product innovation, performance and satisfaction.<br />

MODULAR<br />

FILTRATION<br />

SYSTEMS<br />

Add Mechanical,<br />

Chemical, Heater<br />

Module and UV<br />

Sterilizer as your<br />

needs dictate.<br />

BULKHEAD FITTINGS<br />

Slip or Threaded in all sizes.<br />

INTELLI-FEED<br />

Aquarium Fish Feeder<br />

Can digitally feed up to 12 times daily<br />

if needed and keeps fish food dry.<br />

AIRLINE<br />

BULKHEAD KIT<br />

Hides tubing for any<br />

Airstone or toy.<br />

FLUIDIZED<br />

BED FILTER<br />

Completes the ultimate<br />

biological filtration system.<br />

BIO-MATE®<br />

FILTRATION MEDIA<br />

Available in Solid, or refillable<br />

with Carbon, Ceramic or Foam.<br />

AQUASTEP<br />

PRO® UV<br />

Step up to<br />

new Lifegard<br />

technology to<br />

kill disease<br />

causing<br />

micro-organisims.<br />

LED DIGITAL THERMOMETER<br />

Submerge to display water temp.<br />

Use dry for air temp.<br />

QUIET ONE® PUMPS<br />

A size and style for every need... quiet... reliable<br />

and energy efficient. 53 gph up to 4000 gph.<br />

Visit our web site at www.lifegardaquatics.com<br />

for those hard to find items... ADAPTERS, BUSHINGS, CLAMPS,<br />

ELBOWS, NIPPLES, SILICONE, TUBING and VALVES.<br />

Email: info@lifegardaquatics.com<br />

562-404-4129 Fax: 562-404-4159<br />

Lifegard® is a registered trademark of Lifegard Aquatics, Inc.<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

9

AQUATIC<br />

NOTEBOOK<br />

Betta mahachaiensis from<br />

Samut Sakhon; most populations<br />

have a rounded caudal fin, although<br />

the population in the first description<br />

has a pointed tail.<br />

by Jens Kühne & Chanon Kowasupat<br />

Betta mahachaiensis:<br />

a brackish water Betta<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

Ever since its recent discovery, many aquarists<br />

and scientists have known this brackish water<br />

fighting fish by the name Betta sp. “Mahachai.”<br />

The name refers to the type locality southwest of<br />

Bangkok. Although other names were considered,<br />

to avoid confusion Betta mahachaiensis was<br />

chosen.<br />

Betta mahachaiensis Kowasupat, Panijpan,<br />

Ruenwongsa & Sriwattanarothai 2012 differs<br />

from other fighting fishes of the Betta splendens<br />

group in having two parallel, vertical, bright<br />

green to bluish green stripes on the gill plates.<br />

The eversible gill membrane is red-brown, brown,<br />

or black and has no red spots. The body base<br />

color is dark brown or black. The iridescent body<br />

scales give the fish its characteristic appearance.<br />

The shiny blue-green fin membranes contrast<br />

with the brown-black dorsal, tail, and anal<br />

fin rays. The caudal fin lacks markings. The<br />

brown-black pelvic fins have a blue-and-white<br />

first dorsal ray and bluish-white tips.<br />

The species is distinguished from other similar<br />

types of the Betta splendens group mainly by<br />

DNA studies. For further information, refer to<br />

Sriwattanarothai et al. 2010 and Kowasupat et<br />

al. 2012. According to DNA analysis, Betta splendens<br />

is the closest relative of B. mahachaiensis.<br />

Brackish water swamps<br />

Betta mahachaiensis lives in brackish water habitats<br />

west of Bangkok and in Sakhon Nakhon<br />

province, in pH values of 6.87 to 7.8 and a salinity<br />

of 1.1 to 10.6‰. When Panitvong introduced<br />

the species as Betta sp. “Mahachai” in 2002 on<br />

his Internet portal, siamensis.org, experts were<br />

surprised to learn that a Betta species could permanently<br />

settle in a brackish water habitat. B.<br />

mahachaiensis was initially known only from the<br />

government district Mahachai in Samut Sakhon<br />

and differed from local B. splendens forms. But<br />

Panitvong failed to mention that populations<br />

of B. imbellis from southern Thailand are also<br />

adapted to live in brackish water habitats.<br />

The main habitat of B. mahachaiensis is the<br />

Mae Nam Klong, which flows as part of the Mae<br />

Nam Chin system in Samut Sakhon into the Bay<br />

of Bangkok. The Mae Nam Chin forms a marshy<br />

delta in which the salt-tolerant Nypa palm<br />

grows. These swamps are exposed to the tides<br />

that affect the great Mae Nam Chin, as well as<br />

J. KÜHNE<br />

10

The Wait Is Over<br />

Once upon a time the way to start an<br />

aquarium involved introducing a few<br />

hardy fishes and waiting one to two<br />

months until the tank “cycled.”<br />

Nowadays the startup of aquariums<br />

is so much simpler, and faster too!<br />

BioPronto TM FW contains cultured<br />

naturally occuring microbes that<br />

rapidly start the biological filtration<br />

process. Use it to start the<br />

nitrification cycle in new aquariums<br />

or to enhance nitrification and<br />

denitrification in heavily stocked<br />

aquariums. What are you waiting for<br />

It’s time to make a fresh start.<br />

Two Little Fishies Inc. 1007 Park Centre Blvd.<br />

Miami Gardens, FL 33169 USA www.twolittlefishies.com<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

11

AMAZONAS<br />

Habitat of Betta<br />

the Chao Praya River all the<br />

mahachaiensis. The way to Nonthaburi, about<br />

animals live between the<br />

80 km (50 mi.) inland. The<br />

Nypa palm trees and<br />

Nypa palm is found along all<br />

build their foam nests in<br />

the leaf axils of plants. of these rivers and forms the<br />

habitat of B. mahachaiensis.<br />

The habitats of B. mahachaiensis are periodically<br />

flooded by salt and fresh water. They very rarely dry up<br />

completely. During rainy periods, the swamps are diluted<br />

so much that the residual amount of salt is barely perceptible<br />

at 3 grams per liter (12 g/gal.). Peaking at 13 g/L<br />

(~50 g/gal.), this concentration is tolerated by the fish<br />

only for a short time. The optimum salt concentration<br />

seems to be between 3 and 7 g/L (12–28 g/gal.).<br />

One of us (JK) found a high density of B. mahachaiensis<br />

individuals in freshwater streams near their<br />

inflows into the marsh. In Samut Sakhon there are<br />

freshwater habitats of B. splendens immediately adjacent<br />

to the brackish water habitats of B. mahachaiensis, but no<br />

mixing or hybridization of the species was observed.<br />

Betta mahachaiensis will struggle to survive in the<br />

future, because the known distribution areas are being<br />

swallowed by the giant metropolis of Bangkok. However,<br />

there are other, yet unconfirmed habitats<br />

where this species might be found.<br />

Besides the Samut Sakhon province<br />

already mentioned, these probably include<br />

Samut Songkhram, Samut Prakan,<br />

and the southern parts of Nonthaburi<br />

west of Bangkok, where there are<br />

proven populations. The sporadic finds<br />

in Samut Prakan along the Mae Nam<br />

Chao Phraya south of Bangkok require<br />

confirmation.<br />

Aquarium care<br />

How does B. mahachaiensis differ from<br />

other members of the B. splendens group<br />

in terms of care Do you need to set<br />

up a brackish water aquarium for this<br />

Pair spawning<br />

under the<br />

bubble nest<br />

fish No, not necessarily. One of us (JK) has<br />

already been keeping B. mahachaiensis for about<br />

five years. Some strains are kept permanently in<br />

fresh water without any noticeable impairment.<br />

Any treatment for disease symptoms should<br />

include salt. For prophylaxis, a small amount of<br />

added salt is recommended.<br />

I cannot confirm that the proliferation of<br />

B. mahachaiensis depends on the salt concentration.<br />

The species builds foam nests and spawns<br />

readily in brackish water as well as in fresh<br />

water. These fish seem to react to intermittent<br />

warm and cold periods such as occur in Bangkok;<br />

they go through extremely fertile periods<br />

and then stretches of time when they show no<br />

signs of reproduction. We recommend trying to<br />

breed young adult animals, three to seven months old.<br />

The females in particular have to be sexually mature,<br />

which they indicate with a white genital papilla. You can<br />

set up the aquarium as an underwater jungle with dense<br />

plants, roots, rocks, and clay caves. Many water lilies,<br />

Cabomba, Vallisneria, rushes, Hygrophila, horn ferns, and<br />

mosses tolerate brackish water well.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Kowasupat, C., B. Panijpan, P. Ruenwongsa, and N. Sriwattanarothai.<br />

2012. Betta mahachaiensis, a new species of bubble-nesting fighting fish<br />

(Teleostei: Osphromenidae) from Samut Sakhon province, Thailand. Zootaxa<br />

3522: 49–62.<br />

Kühne, J. 2010. Salzwasserkampffische. Aquaristik Fachmagazin 216:<br />

40–46.<br />

Panitvong, N. 2002. Old article resurrection: Betta sp. Mahachai by Nonn,<br />

April 2002. www.siamensis.org/article/6602.<br />

Sriwattanarothai, N. et al. 2010. Molecular and morphological evidence<br />

supports the species status of the Mahachai fighter Betta sp. Mahachai<br />

and reveals new species of Betta from Thailand. J Fish Biol 77 (2): 414–24.<br />

Sriwattanarothai, N. et al. 2012. Saltwater fighting fish or “Is it too late for<br />

species mahachai” Labyrinth, Newsletter of the Anabantoid Association of<br />

Great Britain 168: 2–11.<br />

J. KÜHNE<br />

12

AQUATIC<br />

NOTEBOOK<br />

A Mexican Crayfish<br />

for Nano Aquariums<br />

Cambarellus patzcuarensis<br />

“Orange”: “berried” female<br />

carrying eggs under abdomen<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

Text and images by Rachel O’Leary The Dwarf<br />

Orange Crayfish, Cambarellus patzcuarensis “Orange,” is<br />

a petite and colorful crustacean that is not as well known<br />

to freshwater aquarists as it should be, but makes a sassy<br />

and active addition to a nano aquarium. Some crayfishes<br />

and “mini lobsters” can be destructive; this species has<br />

proved safe with plants, fishes, and other invertebrates.<br />

In its wild form, it originates in Lake Patzcuaro, about<br />

38 miles southwest of Morelia in Central Mexico. It is<br />

thought that the first orange offspring originated from a<br />

pair of hobbyists from the Netherlands in the late 1990s.<br />

They started becoming available in the United States several<br />

years later, and are casually referred to as CPO.<br />

Cambarellus is a diminutive species, reaching around<br />

1.25 inches (3 cm) at the largest and averaging about 1<br />

inch (2.5 cm). Its native water is relatively cool, averaging<br />

about 72°F (22°C), and is moderately hard. These crayfish<br />

do not require a heater, but because of their size, any intake<br />

on a power filter should be covered with a prefilter sponge.<br />

CPO have an average lifespan of two years, and<br />

warmer temperatures accelerate their growth and breeding.<br />

Adult crayfish molt about twice a year, and young<br />

crayfish generally molt every three to four weeks until<br />

they hit maturity at about 0.7 inch (1.75 cm). They are<br />

fairly easy to breed. The male pins the female to the substrate<br />

and then places his sperm packets near her seminal<br />

receptacle. In a matter of days to weeks, she will molt<br />

and then produce from 20 to 50 eggs, which she attaches<br />

to her pleopod and covers with a protective mucus. The<br />

female carries the babies, even after hatching, until they<br />

are ready to venture out on their own. The adults do not<br />

prey on healthy young, so the survival rate is high.<br />

Feeding is no problem—the crayfish readily take most<br />

prepared or gelatinized foods. Specialized feeding is not<br />

required for the young, although like all invertebrates<br />

they are sensitive to water quality, so care should be taken<br />

not to overfeed. They do well with a varied diet with<br />

both meaty (live or frozen worms and pellets designed<br />

for bottom feeders) and herbivorous foods (vegetables or<br />

algae-based foods), and appreciate having leaf litter for<br />

grazing. Enriched foods containing bio-pigments such as<br />

carotenoids will help maintain bright color.<br />

S. POSTIN<br />

14

Small size and relatively<br />

peaceful disposition make<br />

this an ideal nano-tank<br />

invertebrate.<br />

While peaceful to other inhabitants, these crayfish can threaten each other, especially<br />

after molting, so ample hiding places or cover should be provided utilizing<br />

plants, small pieces of stacked driftwood, or clay or PVC caves. A pair can easily<br />

live in a 5-gallon (20-L) tank or be part of a larger, peaceful community of small<br />

fishes and invertebrates.<br />

This crayfish, which resembles<br />

a miniature lobster, exhibits<br />

interesting behaviors and will<br />

reproduce in the aquarium.<br />

15

Does size matter to you <br />

We bet it does. Trying to clean algae off the glass in a planted aquarium with your typical algae magnet is like running a bull<br />

through a china shop. That’s why we make NanoMag ® the patent-pending, unbelievably strong, thin, and flexible magnet for cleaning<br />

windows up to 1/2” thick. The NanoMag flexes on curved surfaces including corners, wiping off algal films with ease, and it’s so much fun to<br />

use you just might have to take turns. We didn’t stop there either- we thought, heck, why not try something smaller So was born MagFox ® ,<br />

the ultra-tiny, flexible magnetically coupled scrubber for removing algae and biofilms from the inside of aquarium hoses.<br />

Have you got us in the palm of your hand yet<br />

www.twolittlefishies.com<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

16

AQUATIC<br />

NOTEBOOK<br />

Wild-type Enneacampus<br />

ansorgii collected by Ted Judy<br />

in Gabon.<br />

This new captive-bred red form is now<br />

reaching the aquarium trade.<br />

UPPER: TED JUDY; LOWER: MIKE TUCCINDARDI/SEGREST FARMS<br />

by Matt Pedersen<br />

Arriving soon: Tank-raised<br />

African Freshwater Pipefish<br />

The African Freshwater, or Dwarf Red Snout Pipefish, Enneacampus ansorgii,<br />

is exotic and rare enough that even expert aquarists assume it is more at<br />

home on a coral reef than in a clear freshwater stream 100 miles from the<br />

ocean. Now this sometimes brilliantly pigmented little species is being bred<br />

in captivity and is starting to enter the aquarium trade.<br />

Husbandry accounts suggest that wild specimens are certainly difficult<br />

to keep alive, generally requiring live foods such as brine shrimp, blackworms,<br />

Daphnia, cyclops, and even the fry of livebearers. Wolfgang Löll<br />

makes a compelling argument that live glassworms are the best food for<br />

pipefishes such as E. ansorgii because they survive for several days in the<br />

aquarium and will tolerate slightly brackish water.<br />

Aquarium literature, where this fish was formerly known as Sygnathus<br />

ansorgii (Boulanger, 1910), generally suggests that the inclusion of salt is<br />

helpful for this species, although it is clear that some populations of the<br />

species have no contact with anything remotely close to a marine environment.<br />

A general rule is to house them in a small species tank in slightly<br />

brackish water or a .5-percent sea salt solution. Their reported range<br />

includes the Ogooue River of Gabon, Cameroon, and Equatorial Guinea.<br />

(American aquarist and award-winning breeder Ted Judy reports collecting<br />

males brooding eggs in pure, freshwater river conditions in Gabon.) They<br />

produce relatively large offspring.<br />

In March of 2013, Segrest Farms in Gibsonton, Florida, announced the<br />

arrival and almost immediate sell-out (within 24 hours) of captive-bred E.<br />

ansorgii. These fish came in at a 3–4-inch (7.5–10-cm) size, which is close<br />

TMAMAZONAS<br />

17

AQUATIC<br />

NOTEBOOK<br />

to the maximum adult size of 5–6 inches (12–15 cm)<br />

and were not produced by Florida or Asian fish farms, as<br />

many aquarists suspected, but actually made their way to<br />

North America from the Czech Republic via a small-scale<br />

Manage Your Own<br />

Subscription<br />

It’s quick and user friendly.<br />

Go to www.AmazonasMagazine.com.<br />

Click on the SUBSCRIBE tab.<br />

specialist breeder.<br />

While this certainly isn’t the first time this species<br />

has been successfully bred in captivity, this commercial<br />

availability represents a potential shift in our perception<br />

of the species. Just as captive-bred<br />

marine seahorses are infinitely<br />

better suited to captive foods<br />

and life in an aquarium, these<br />

captive-bred E. ansorgii were feeding<br />

on frozen Cyclops (CYCLOP-<br />

EEZE®), and might be weaned to<br />

small, high-protein pellet foods or<br />

potentially even flake food. Truly,<br />

commercially viable captive-bred<br />

specimens may well redefine this<br />

species.<br />

Segrest’s Mike Tuccinardi suggests<br />

that “it’s unlikely they’ll be a<br />

regular stock item, but it wouldn’t<br />

be out of the question to see them<br />

in some of the more specialized<br />

local fish stores across the country<br />

over the next few months. We<br />

are sold out right now, but we’ll<br />

be bringing in more soon.” He<br />

adds, “As for care, treat them as<br />

you would their saltwater cousins—avoid<br />

boisterous or aggressive<br />

tankmates, give them lots of<br />

cover, and feed them frequently.”<br />

Here you can:<br />

● Change your address<br />

● Renew your subscription<br />

● Give a gift<br />

● Subscribe<br />

● Buy a back issue<br />

● Report a damaged or missing issue<br />

Other options:<br />

EMAIL us at:<br />

service@amazonascustomerservice.com<br />

CALL: 570-567-0424<br />

Or WRITE:<br />

AMAZONAS Magazine<br />

1000 Commerce Park Drive, Suite 300<br />

Williamsport, PA 17701<br />

ON THE INTERNET<br />

http://diszhal.info/english/livebearers/en_<br />

Syngnathus_pulchellus.php#ixzz2NbnQTyG5<br />

http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/<br />

full/167999/0<br />

http://www.aqualog.de/Aqualog/news/<br />

web90/Seite11-13e.pdf<br />

Correction<br />

The images accompanying<br />

the article, Dicrossis maculatus:<br />

Breeding the Checkerboard<br />

Cichlid by David<br />

Magid (AMAZONAS, Mar/<br />

Apr 2013, page 60), were<br />

taken by Noah Magid, not<br />

David Magid. AMAZONAS<br />

regrets the error.<br />

18

24/7<br />

VISIT OFTEN:<br />

• Web-Special Articles<br />

• Aquatic News of the World<br />

• Aquarium Events Calendar<br />

• Links to Subscribe, Manage<br />

Your Subscription, Give a<br />

Gift, Shop for Back Issues<br />

• Messages & Blogs from<br />

AMAZONAS Editors<br />

• Coming Issue Previews<br />

• New Product News<br />

• Links to Special Offers<br />

www.Reef2Rainforest.com<br />

Our new website is always open, with the latest news and<br />

content from AMAZONAS and our partner publications.<br />

HOME of AMAZONAS, CORAL, & MICROCOSM BOOKS<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

19

AQUATIC<br />

NOTEBOOK<br />

Male Black Ruby Barb,<br />

now known as Pethia<br />

nigrofasciata<br />

New names for old friends<br />

Hans-Jürgen Bäselt Nothing is as constant as change. This applies especially to the taxonomy of<br />

fishes, and earlier this year some familiar barb species from India and Sri Lanka were caught up in a sea<br />

of revisions. Pethiyagodha et al. revised the large “dumpster” genus Puntius and divided it into several<br />

newly established genera. Nine species of the former Puntius filamentosus group were placed in the<br />

genus Dawkinsia. The Melon Barb (formerly Puntius fasciatus, now Dravidia fasciata) was renamed and<br />

put together with four other species in the genus Dravidia. The third new genus, Pethia, was erected to<br />

include some very popular species, such Pethia conchonius, P. padamya, P. ticto, and many more. Pethia<br />

nigrofasciata, known to many as the Black Ruby Barb, belongs in the genus as well.<br />

The Melon Barb is now<br />

called Dravidia fasciata.<br />

The Filament Barb<br />

Dawkinsia filamentosa was<br />

reclassified as well.<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

H.-G. EVERS<br />

20

The world is yours.<br />

<br />

The earth is composed of water—71.1% to be exact. But when it comes to<br />

tropical fish, we’ve really got it covered. Not only with exotic varieties from<br />

around the globe, but with the highest level of quality, selection and vitality.<br />

Ask your local fish supplier for the best, ask for Segrest.<br />

Say Segrest. See the best. QUALITY, SERVICE & DEPENDABILITY<br />

<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

21

COVER<br />

STORY<br />

Killifish gems in the genus<br />

Aphyosemion from the <strong>Congo</strong><br />

River basin, in the second-largest<br />

rainforest on earth.<br />

Aphyosemion<br />

in the <strong>Congo</strong> Basin<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

by Jouke van der Zee & Rainer Sonnenberg African killifishes are some of the most coveted<br />

and beautiful of tropical fishes, but they are found in a place so vast, untamed, and fraught<br />

with violence that they are neither collected nor studied as frequently as many enthusiasts<br />

would like. Our interest in these fishes has focused on the genus Amphyosemion, which is very<br />

likely an assemblage of more or less related species groups.<br />

22

The <strong>Congo</strong>, 2,717 miles (4,374 km) long<br />

and up to 755 feet (230 m) deep, is the<br />

deepest and second-largest river in Africa,<br />

and in terms of drainage area and water<br />

flow the second-largest river in the world,<br />

after the Amazon. Its drainage encompasses<br />

not only the two <strong>Congo</strong> states (<strong>Congo</strong><br />

Republic and Democratic Republic of the<br />

<strong>Congo</strong>, or DRC) but also parts of Angola,<br />

Burundi, Cabinda, Cameroon, Rwanda,<br />

Zambia, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, and the<br />

Central African Republic.<br />

The <strong>Congo</strong> already existed when the<br />

dinosaurs ruled the earth, although at<br />

that time it still emptied into the Indian<br />

Ocean. The Rufiji in Tanzania is possibly<br />

the former lower course of the ancient<br />

<strong>Congo</strong> river. During the Pliocene (around<br />

1.8–5.3 million years ago) the East African<br />

highland plateau came into being and the<br />

flow of the ancient <strong>Congo</strong> in an easterly<br />

direction was blocked. Traces of former links to the<br />

east can still be detected today: depending on water<br />

level, the East African Lake Tanganyika still empties in<br />

the direction of the <strong>Congo</strong> via the Lukuga, and there is<br />

evidence that the Malagarasi, for example, used to be<br />

part of the <strong>Congo</strong> drainage.<br />

After the blocking of the eastern lower course, the<br />

<strong>Congo</strong> rainforest could no longer drain away its water,<br />

and in time a vast lake developed in central Africa.<br />

It is thought that by one to two million years ago<br />

the mountains separating the lake from the Atlantic<br />

Ocean had been eroded to such an extent that a link<br />

between the inland sea and a westward-flowing river<br />

Above: The map shows<br />

the distribution of<br />

the Aphyosemion s. l.<br />

species in the <strong>Congo</strong><br />

Basin.<br />

Right: Dr. Emmanuel<br />

Vreven, ichthyologist<br />

at Belgium’s Royal<br />

Museum for Central<br />

Africa (RMCA), with<br />

his assistant. You need<br />

more than a net to<br />

collect fishes in the<br />

<strong>Congo</strong>.<br />

MAP: J. V. D. ZEE; MIDDLE: RMCA; BOTTOM: E. VREVEN (RMCA)<br />

Left:<br />

Location for<br />

Aphyosemion<br />

christyi in<br />

the Okapi<br />

Wildlife<br />

Reserve.<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

23

Lake Mai Ndombe. The surrounding<br />

areas are very swampy and difficult to<br />

access.<br />

“Aphyosemion” labarrei from Nenga Kibuka, Ngufu River (AVD 2011).<br />

“Aphyosemion” labarrei from Kingembe, Inkisi River (AVD 2011).<br />

Hard-to-Reach Fishes<br />

In terms of fish collections, the <strong>Congo</strong><br />

Basin is one of the least explored<br />

regions on Earth. This is mainly due to<br />

the immense size of the basin, the lack<br />

of infrastructure, and the very unstable<br />

political situation. Systematic study of<br />

the fish fauna of the <strong>Congo</strong> began in<br />

the colonial period; the works of Belgian<br />

zoologist George Albert Boulenger<br />

are particularly worthy of note. After<br />

1960, the end of the Belgian colonial<br />

period, many fish collections were<br />

made by Belgian biologists and missionaries.<br />

Nevertheless, large parts of the<br />

basin have never been scientifically<br />

studied. Aquarists, especially killifish<br />

specialists, rarely travel the eastern and<br />

southern <strong>Congo</strong> Basin. In the 1980s,<br />

Heiko Bleher explored Lake Fwa, in the<br />

drainage of the Kasai and the middle<br />

<strong>Congo</strong>. In 1985, Dutchman Jan Pap<br />

and two Germans, Winfried Stenglein<br />

and Wolfgang Grell, visited the<br />

northeastern part of the Democratic<br />

Republic of the <strong>Congo</strong> (DRC). This is<br />

probably one of the best documented<br />

collecting trips. The western part of the<br />

<strong>Congo</strong> Basin has been collected only<br />

in 1978 by Huber and in 1991 by a<br />

Dutch-Belgian team consisting of De<br />

Waegeneer, Vlym, and Van der Berg. By<br />

contrast, other African countries, such<br />

as Cameroon and Gabon, have been<br />

visited many times by aquarists in the<br />

past four decades.<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

Raddaella batesii from Equatorial<br />

Guinea (EQG 06/2).<br />

came into being. From then on the lake emptied westward<br />

from Malebo Pool to the Atlantic Ocean via its current<br />

lower course. But perhaps there were already earlier<br />

outlets in the direction of the Atlantic further to the<br />

north, for example via the Ogooue. There are still many<br />

unanswered questions to be researched here.<br />

The remains of the ancient lake can still be found in<br />

the central <strong>Congo</strong> Basin, for example, Lake Tumba and<br />

Killifishes of the <strong>Congo</strong> Basin<br />

Because the genus Aphyosemion as<br />

usually understood is an assemblage of<br />

various species groups, in this article<br />

we will classify only the species of the<br />

Aphyosemion elegans species group as<br />

Aphyosemion or Aphyosemion s. s. (sensu strictu, in the<br />

strict or narrow sense).<br />

This group includes the type species of the genus,<br />

Aphyosemion castaneum. Other species groups already<br />

have an established name (usually described as a subgenus).<br />

In the event that there is still no (sub-) genus<br />

name described, the genus name will be given in quotes.<br />

This usage may be known to cichlid enthusiasts from the<br />

TOP & MIDDLE: K. STEHLE: BOTTOM: W. EIGELSHOFEN<br />

24

former catch-all genus “Cichlasoma.” When we mean the<br />

entire erstwhile genus Aphyosemion, we will use the term<br />

Aphyosemion s. l. (sensu lato, in the broad sense).<br />

At present, 22 Aphyosemion s. l., 2 Fenerbahce, 7<br />

Epiplatys, 5 Nothobranchius (family Nothobranchiidae),<br />

and 21 lampeyes (family Poeciliidae) are described from<br />

the <strong>Congo</strong> Basin. Even so, the killifish fauna of this<br />

region is only fragmentarily known, but that is changing<br />

quickly. Several institutions, including the Royal Museum<br />

for Central Africa (RMCA) in Belgium, the Zoologische<br />

Staatssammlung München (ZSM) in Munich, and the<br />

American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New<br />

York, have collaborated on expeditions with local biologists<br />

and students. In particular, the central <strong>Congo</strong> Basin,<br />

the lower <strong>Congo</strong>, and the northeastern DRC have been<br />

explored by various ichthyologists in recent years.<br />

All these expeditions have discovered a number of<br />

noteworthy and hitherto undescribed fishes, including<br />

several killifish species. For example, a southern tributary<br />

of the Kasai was recently investigated by Jose Justin<br />

Mbimbi Mayi Munene, a student at the University of<br />

Kinshasa and a member of the AMNH <strong>Congo</strong> project for<br />

fieldwork and research on the fishes of the DRC. He collected<br />

not only an unusual black Epiplatys,<br />

but also two as-yet-undescribed<br />

Hypsopanchax species in a relatively<br />

small area in the middle section of the<br />

Lulua River.<br />

The recently described “Aphyosemion”<br />

teugelsi was found in museum<br />

material collected back in 1939 from<br />

a southwestern tributary of the Kasai<br />

near the border with Angola. This indicates<br />

the likelihood that in the future<br />

we can expect to see more new species<br />

from the southern tributaries of the<br />

<strong>Congo</strong> Basin.<br />

splendidum achieved this in the northern <strong>Congo</strong> Basin,<br />

and the species has spread out from there for more<br />

than 600 miles (1,000 km). By contrast, “Aphyosemion”<br />

escherichi has penetrated only a few kilometers into the<br />

extreme west of the <strong>Congo</strong> drainage. The species was described<br />

from specimens caught at the foot of the Crystal<br />

Mountains in Gabon. “Aphyosemion” microphtalmum<br />

Lambert & Géry, 1968 (type locality: PK 85 on the Route<br />

Pointe Noire to Sunda, <strong>Congo</strong> Republic) and “Aphyosemion”<br />

simulans Radda & Huber, 1976 (type locality: stream<br />

on the road from Libreville to Cap Esterias, Gabon) are<br />

currently regarded as synonyms. “Aphyosemion” escherichi<br />

is distributed along the coast from northern Gabon to<br />

the lower course of the <strong>Congo</strong>.<br />

“Aphyosemion” labarrei (Poll 1951) was described<br />

from the Inkisi, a southern tributary of the lower <strong>Congo</strong>.<br />

A few years ago Soleil Wamuini, a doctoral candidate at<br />

the University of Liege in Belgium, who was supervised<br />

by staff at the RMCA, prepared an inventory of the fish<br />

fauna of the Inkisi (Wamuini et al. 2010), and in the<br />

process discovered several previously unknown species<br />

related to “A.” labarrei. Their description is now in<br />

progress. Apart from two differently colored Aphyosemion<br />

“Aphyosemion” escherichi from Mayombe, collected<br />

by A. Van Deun (May 2011) in Bas <strong>Congo</strong>.<br />

Aphyosemion sensu lato<br />

Compared with the region known as<br />

Lower Guinea (Equatorial Guinea,<br />

Gabon, Cameroon, and the coastal<br />

regions of the <strong>Congo</strong> Republic, the<br />

DRC, and Cabinda), Aphyosemion s. l.<br />

are poorly represented in the <strong>Congo</strong><br />

Basin. Apart from 18 members of the<br />

A. elegans group (or Aphyosemion sensu<br />

stricto), only four additional species<br />

occur there: “Aphyosemion” escherichi,<br />

“A.” labarrei, “A.” teugelsi, and Raddaella<br />

splendidum.<br />

“Aphyosemion” escherichi (Ahl<br />

1924) is, like Raddaella splendidum,<br />

a member of the fish fauna of Lower<br />

Guinea that has managed to penetrate<br />

into the <strong>Congo</strong> drainage. Raddaella<br />

H. OTT<br />

Aphyosemion castaneum (HZ<br />

85/8), north of Kisangani.<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

25

AMAZONAS<br />

cf. cognatum populations, no further killifishes have been<br />

collected.<br />

In May 2011, Armand Van Deun, a Belgian physician<br />

who regularly works in the <strong>Congo</strong>, brought back two new<br />

“Aphyosemion” labarrei populations that are now being<br />

bred by aquarist friends and distributed more widely.<br />

They come from two sites to the north and east of the<br />

type locality. The holotype in the RMCA differs considerably<br />

from the “Aphyosemion” labarrei aquarium strains<br />

known to date. It is a broader, compressed species with<br />

relatively long teeth and almost completely dark gray to<br />

black fins. Although the color pattern of “Aphyosemion”<br />

Aphyosemion chauchei (Obeya, RPC 91/6).<br />

Aphyosemion christyi (HZ 85/14), photographed in 1988.<br />

Aphyosemion cognatum from Kwambila.<br />

labarrei resembles that of “Aphyosemion” zygaima, which<br />

lives on the other side of the <strong>Congo</strong>, DNA studies show<br />

that the closest relatives are found in a group consisting<br />

of Aphyosemion, Raddaella, and Mesoaphyosemion (the<br />

“Aphyosemion” cameronense species group), as well as the<br />

“Aphyosemion” coeleste and the “Aphyosemion” wildekampi<br />

species groups (Collier 2007, Murphy & Collier 1999).<br />

“Aphyosemion” teugelsi (Van der Zee & Sonnenberg)<br />

was discovered in 2010 in the RMCA collection. This<br />

species is found in a very remote area in the south of<br />

the DRC, close to the border with Angola, at an altitude<br />

of 3,280 feet (1,000 m). Only Kathetys elberti and<br />

K. bamilekorum have been found at<br />

greater altitude. Although “Aphyosemion”<br />

teugelsi exhibits a superficially<br />

similar color pattern to A. congicum,<br />

the morphology is very different. This<br />

species is distinguished from those of<br />

the A. elegans group by the dorsal fin,<br />

which begins further forward and is<br />

relatively broad at the base, a larger<br />

head with relatively large eyes, and a<br />

more strongly upcurved dorsal profile.<br />

We were unable to assign it to any of<br />

the known species groups because of<br />

the morphological differences. Perhaps<br />

this fish belongs to a species group that<br />

lives in the hitherto rather inaccessible<br />

mountains of the southern <strong>Congo</strong> and<br />

northern Angola.<br />

Raddaella splendidum (Pellegrin<br />

1930). The Raddaella species are the<br />

only annual Aphyosemion s. l. They<br />

were long assigned to the genus Fundulopanchax,<br />

but DNA study shows that<br />

they definitely belong to Aphyosemion s.<br />

l. It is, however, unclear whether Raddaella<br />

is a monotypic genus with only<br />

one species, R. batesii, or whether R.<br />

kunzi and R. splendidum are also valid<br />

species. Raddaella species are the only<br />

Aphyosemion s. l. that occur in both<br />

Lower Guinea and the <strong>Congo</strong> Basin.<br />

The two species previously mentioned,<br />

which also occur in the <strong>Congo</strong> drainage,<br />

are restricted to western tributaries<br />

of the lower <strong>Congo</strong>. Raddaella are<br />

widespread in southern Cameroon<br />

and northern Gabon. To date, very<br />

few localities are known for them in<br />

Equatorial Guinea, the <strong>Congo</strong> Republic,<br />

and the DRC. Perhaps they reached<br />

the <strong>Congo</strong> Basin via the Likouala in<br />

the northwest.<br />

The Likouala has tributaries that<br />

drain the southeastern part of Camer-<br />

TOP: W. EIGELSHOFEN; MIDDLE: J.V.D. ZEE; BOTTOM: H. OTT<br />

26

oon. It is not unlikely that the change<br />

in the direction of flow of the Dja,<br />

which originally drained to the Atlantic<br />

coast, was originally responsible for<br />

the spread of Raddaella into the <strong>Congo</strong><br />

Basin via the Ngoko, a tributary of<br />

the Likouala. Raddaella then spread<br />

upstream in an easterly direction. That<br />

wouldn’t have been difficult—in this region<br />

the <strong>Congo</strong> has a drop of only 328<br />

feet (100 m) over a distance of 1,242<br />

miles (2,000 km), so it is more like a<br />

lake than a river.<br />

“Aphyosemion” escherichi from Mayombe,<br />

collected by A. Van Deun (May 2011) in Bas <strong>Congo</strong>.<br />

TOP: K. STEHLE; BOTTOM: H. OTT<br />

Aphyosemion sensu stricto<br />

This group contains the majority of the<br />

Aphyosemion s. l. species of the <strong>Congo</strong><br />

Basin. They are broadly identical in<br />

morphology but differ considerably in<br />

the coloration of males and in their<br />

DNA. Eighteen species are currently<br />

recognized. The distribution of most<br />

species is very complex and exhibits a<br />

mosaic-like, parapatric pattern. They<br />

sometimes also occur sympatrically,<br />

that is, in the same river system. However,<br />

in only a few cases to date are two<br />

species known to be syntopic (found at<br />

the same site).<br />

Aphyosemion castaneum (Myers 1924) was described<br />

by the author from preserved material collected by an<br />

American expedition to the <strong>Congo</strong>. He established that<br />

the genus used in those days for more slender killifishes<br />

of Africa, Haplochilus (Aplocheilus, now restricted to Indian<br />

and Asian species), didn’t constitute a homogenous<br />

group, and straightaway described the genus Aphyosemion.<br />

His newly described species A. castaneum was<br />

designated the type species of the genus. Authors such<br />

as Scheel, Radda, and Wildekamp regard A. castaneum as<br />

a synonym of A. christyi, but it has recently been shown<br />

that the occurrence of A. christyi is restricted to the<br />

eastern part of the <strong>Congo</strong> Basin at altitudes of 1,640 feet<br />

(500 m) and up, and that A. castaneum represents a valid<br />

species (Van der Zee & Huber 2006).<br />

Aphyosemion chauchei (Huber & Scheel 1981) is<br />

a “blue” species with blue dorsal and caudal fins and<br />

a yellow anal fin, found in a very limited area in the<br />

<strong>Congo</strong> Republic. In the west and south it is replaced by<br />

a “yellow” species with yellow fins, shown on the map<br />

as A. “schioetzi.” The body forms of A. “schioetzi” and<br />

A. chauchei are identical. They are relatively small and<br />

slender Aphyosemion species, unlike A. schioetzi, which is<br />

a comparatively robust species. Aphyosemion schioetzi and<br />

A. “schioetzi” are separated by a large distributional gap,<br />

and we believe that they do not represent a single species.<br />

Whether A. “schioetzi” is an as-yet-undescribed species<br />

Aphyosemion castaneum (HZ 85/8), north of Kisangani.<br />

remains unclear at present (see also A. decorsei). With<br />

one exception, all known locations for A. chauchei lie in<br />

the southern Likouala basin. A population from Olombo,<br />

which differs in color pattern from the Likouala populations,<br />

lives in the Alima drainage.<br />

Aphyosemion christyi (Boulenger 1915) is restricted to<br />

the Ituri forest region northeast of Bafwassende. Aphyosemion<br />

margaretae (Fowler 1936) is regarded as a synonym<br />

(Van der Zee & Huber 2006). Wild-caught specimens of<br />

this species have a very typical violet coloration. Even in<br />

poor-quality photos the species can be easily identified on<br />

this basis. Aphyosemion christyi is very widespread in the<br />

Okapi Faunal Reserve. Several collections have been made<br />

there recently by Emmanuel Vreven (RMCA) and his<br />

colleagues. So far, this is the only species of the A. elegans<br />

group that can be identified by its meristics (countable<br />

traits), as on average it has more rays in the dorsal fin<br />

than the other species.<br />

Aphyosemion cognatum (Meinken 1951) has a very<br />

large distribution in the southern <strong>Congo</strong>. The distance<br />

from west to east is almost 559 miles (900 km). At the<br />

same time, the species exhibits numerous different phenotypes.<br />

The DNA of an aquarium strain of one of the<br />

eastern populations (Lake Fwa) was studied by Murphy<br />

& Collier (1999). It turned out that were no differences<br />

between the Lake Fwa and the Kinsuka populations (Van<br />

der Zee & Sonnenberg 2011). Hence it is possible that<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

27

AMAZONAS<br />

Aphyosemion lamberti (BSWG 97/9).<br />

Aphyosemion lujae, the type from Kondue on the Sankuru.<br />

Aphyosemion musafirii (AVD 1), 4.3 miles (7 km) north of Ubundu, wild-caught male,<br />

2007.<br />

since their importation the two strains have been mixed<br />

in the killifish hobby or incorrectly identified. More study<br />

is needed to demonstrate whether this is actually a single<br />

species with a large distribution or several species with a<br />

parapatric distribution, inhabiting adjoining ranges.<br />

Aphyosemion congicum (Ahl 1924). Genetic research<br />

(surprisingly) places this species in a group with A. castaneum<br />

and A. musafirii (Van der Zee & Sonnenberg 2011).<br />

The species is known from only two sites in the southern<br />

<strong>Congo</strong>; both were discovered by Radda<br />

in 1982. The species description is<br />

based on specimens with the locality<br />

given as “<strong>Congo</strong>.” At present, A.<br />

melanopteron Goldstein & Ricco 1970,<br />

whose type locality is also unknown,<br />

is regarded as a synonym. By contrast,<br />

Huber is of the opinion that the description<br />

by Ahl shows that A. congicum<br />

differs from A. melanopteron, as the<br />

former supposedly has many more red<br />

dots on the side (2007, online version<br />

www.killi-data.org). Unfortunately, the<br />

preserved type specimens in general no<br />

longer exhibit any traces of coloration.<br />

Aphyosemion decorsei (Pellegrin<br />

1904) is one of the most confused<br />

species of the A. elegans group. The<br />

status of A. decorsei has long been<br />

debated. Poll placed it in the genus<br />

Epiplatys, and in the description of<br />

Haplochilus decorsei Pellegrin even<br />

assumed a close relationship with<br />

Aplocheilichthys spilauchen. Myers<br />

(1924) tentatively placed the species<br />

in Aphyosemion. Scheel, Huber, and<br />

Wildekamp have examined all the types<br />

and confirmed Myers’s view. The type<br />

specimens originate from the south<br />

of the Central African Republic and<br />

are in poor condition, without any<br />

remaining traces of coloration. Huber<br />

suggests that A. decorsei has very few<br />

red dots on the side and is conspecific<br />

with A. polli; the latter would then be<br />

a synonym. Wildekamp (1993), by<br />

contrast, is convinced that A. decorsei<br />

has numerous dots on the side, based<br />

on the light spots on the scales of the<br />

syntypes. After preservation in formalin<br />

and subsequent transfer into alcohol,<br />

red pigments leave behind corresponding<br />

areas that are lighter than the body<br />

base coloration. Aphyosemion polli has<br />

not only few spots on the side, but also<br />

very few (or none at all) on the anal<br />

fin. These are arranged at the base of<br />

the fin. In the original description of A. decorsei Pellegrin<br />

wrote that the dorsal, anal, and ventral fins are covered<br />

with small, more or less numerous carmine red dots. We<br />

concur with Wildekamp’s argument: A. decorsei is a species<br />

with numerous dots, at least on the anal fin. But that<br />

doesn’t solve the problem of whether A. decorsei is a “yellow”<br />

fish like A. “schioetzi” and A. sp. RCA 3, collected by<br />

Pratt in 1983, or a “blue” fish like A. sp. “Lobaye.” Only<br />

further collections and photos of live fishes from the area<br />

TOP & MIDDLE: J.V.D. ZEE; BOTTOM: H. OTT<br />

28

H. OTT<br />

of the type locality will permit unequivocal clarification.<br />

Aphyosemion elegans (Boulenger 1899) is not identical<br />

with the species known to aquarists for decades under<br />

this name. In the 1950s the Belgian aquarist Lambert<br />

introduced killifishes from Boende labeled A. elegans into<br />

the aquarium hobby. We (Van der Zee & Sonnenberg<br />

2011) argue instead that Lambert’s fishes (which we<br />

term A. sp. “Cuvette”) do not agree with Boulenger’s description<br />

of A. elegans. This incorrectly identified species<br />

has a very characteristic dark red dorsal fin, which is also<br />

clearly recognizable in preserved specimens. Boulenger<br />

doesn’t mention this character in the text of the description<br />

of A. elegans, and no dark dorsal fin is shown in the<br />

illustration accompanying the description. Uli Schliewen<br />

brought what is probably the real A. elegans to Germany<br />

from Mbombokonda. Aphyosemion sp. “Bombala” also<br />

represents A. elegans, as does a commercial importation<br />

in 2006 from the Tshuapa in the Boende region. Aphyosemion<br />

elegans and the species recently described by us as<br />

A. pseudoelegans occur sympatrically in the central <strong>Congo</strong><br />

Basin.<br />

Aphyosemion ferranti (Boulenger 1910) is currently<br />

known only from preserved specimens from various<br />

locations in the southeast of the <strong>Congo</strong>. The species can<br />

(purportedly) be identified very easily by the red longitudinal<br />

band on the side of the body. But<br />

there is at least one further, undescribed<br />

species from the northern <strong>Congo</strong><br />

with a similar band. Perhaps a better<br />

character is the unusual, asymmetric<br />

color pattern on the caudal fin: spotted<br />

above, without spots below. The species<br />

also differs in further characters from<br />

the other Aphyosemion species and may<br />

belong in another species group, maybe<br />

with “Aphyosemion” teugelsi. New collections<br />

of both species, above all of<br />

live specimens and DNA samples, may<br />

solve many unanswered questions.<br />

Aphyosemion lamberti (Radda &<br />

Huber 1977) is widely distributed in<br />

Gabon. Aphyosemion lamberti and A.<br />

rectogoense are sibling species and, so<br />

far, the only members of the genus<br />

Aphyosemion that occur outside the<br />

<strong>Congo</strong> Basin. To date it remains<br />

unknown whether the genus Aphyosemion<br />

colonized the <strong>Congo</strong> drainage<br />

from southeast Gabon or the ancestors<br />

of these two species came from the<br />

<strong>Congo</strong> Basin. DNA results so far seem<br />

to point to the second possibility. Like<br />

all other members of the species group,<br />

A. lamberti is also a rainforest dweller,<br />

while A. rectogoense is the only savanna<br />

dweller.<br />

Aphyosemion lefiniense (Woeltjes 1984) is restricted<br />

to the Lefini on the west bank of the <strong>Congo</strong> in the <strong>Congo</strong><br />

Republic. After the first collection, on which the description<br />

was based, it wasn’t until 2005 that staff from the<br />

RMCA were able to find this species again at various sites<br />

in the Lefini. This species is very rare in the aquarium<br />

hobby, and the captive population may even have died<br />

out completely a few years ago.<br />

Aphyosemion lujae (Boulenger 1911) is currently<br />

known only from preserved specimens that originated<br />

from the Sankuru system, a tributary of the Kasai, at<br />

Kondue. Aphyosemion ferranti is also found near Kondue.<br />

This species was, however, also collected at various places<br />

around Bena Tshadi in 1974 and 1979. It remains unclear<br />

whether the currently known locations for A. ferranti and<br />

A. lujae in the vicinity of Kondue represent the southern<br />

boundary of the distribution of Aphyosemion, or whether<br />

the southern tributaries of the Kasai harbor additional,<br />

as-yet-unknown species.<br />

Aphyosemion musafirii (Van der Zee & Sonnenberg<br />

2011) was only recently described. The species<br />

was caught by Armand van Deun (AVD) in 2007, and<br />

specimens from two populations were brought back alive<br />

to Europe. These fishes have been maintained and bred<br />

in the hobby as A. sp. AVD 1 and AVD 2. Although the<br />

Aphyosemion plagitaenium from Epoma (RPC 91/1).<br />

Aphyosemion pseudoelegans<br />

from Boende, imported in<br />

2002.<br />

AMAZONAS<br />

29

AMAZONAS<br />

Aphyosemion rectogoense from site PEG 95/16.<br />

Aphyosemion<br />

pseudoelegans from<br />

Boende, imported in<br />

2002.<br />

Aphyosemion schioetzi from Kintete.<br />

species looks more like a member of the A. cognatum<br />

group (numerous red dots on the sides of the body in<br />

males), its closest relative is A. castaneum, which lives on<br />

the other side of the <strong>Congo</strong>. DNA indicates that the two<br />

species may have been separated as long ago as one to<br />

two million years.<br />

Aphyosemion plagitaenium (Huber 2004) was discovered<br />

in 1991 during a collecting<br />

trip by Dutch and Belgian aquarists<br />

to the <strong>Congo</strong> Republic. It was known<br />

as A. sp. “Epoma RPC 91/1” prior to<br />

its description. This species, which<br />

has a remarkable color pattern, is so<br />

far known from only a single location<br />

in the system of the Mambili River, a<br />

tributary of the Likouala.<br />

Aphyosemion polli (Radda & Pürzl<br />

1987) was described from N’djili (Z<br />

82/26), close to the international airport<br />

near Kinshasa in the DRC. Many<br />

authors regard A. polli as a synonym of<br />

A. schoutedeni or A. decorsei, but we are<br />

convinced that A. polli is a valid species<br />

(see A. schoutedeni and A. decorsei).<br />

This species (if A. cf. polli is included,<br />

see map) is widespread in the <strong>Congo</strong><br />

Basin. Collections known to date<br />

took place along the Uele, Ubanghi,<br />

and <strong>Congo</strong>. Apart from a number of<br />

populations in the north of the <strong>Congo</strong><br />

Republic, which were collected by Huber,<br />

and a population from a southern<br />

tributary of the Kasai, all collections<br />

have been made relatively close to the<br />

main rivers. Unfortunately, no photos<br />

of Huber’s collections were published,<br />

so the identification of the species<br />

cannot be checked. The preserved<br />

specimens from the southern location<br />

in the Kasai drainage exhibit the same<br />

color pattern as A. polli, but the dots<br />

on the sides aren’t round; they look<br />

like little crosses. Until new collections<br />

permit a definite identification, the<br />

unclear status of this fish should be<br />

expressed by the designation A. cf. polli.<br />

Aphyosemion pseudoelegans<br />

(Sonnenberg & Van der Zee 2012)<br />

is a species already known in the<br />

aquarium hobby, but has hitherto been<br />

incorrectly labeled as A. elegans (see<br />

A. elegans). It is known from several<br />

locations south of the <strong>Congo</strong> in the<br />

central <strong>Congo</strong> Basin and is found there<br />

sympatric and, in some cases, also syntopic<br />

with A. elegans, A. cf. castaneum,<br />

and a further, not-yet-described Aphyosemion species. Its<br />

characteristic characters are the dark red coloration of<br />

the dorsal fin (versus red dots on a light background in<br />

A. elegans) and an asymmetric sequence in the color pattern<br />

of the fin edges of the caudal fin.<br />

Aphyosemion rectogoense (Radda & Huber 1977)<br />

is the sister species of A. lamberti on the basis of DNA<br />

TOP & MIDDLE: H. OTT; BOTTOM: HANSSENS (RMCA)<br />

30

study. Ten localities are known in the<br />

hobby and all populations are very<br />

similar. There are, to date, only three<br />

collections in museums. This is the<br />

only Aphyosemion s. l. species on the<br />

IUCN Red List. This because of its<br />

small distribution region in the upper<br />

Lékoni-Djouya and the upper Mpassa in<br />

the Ogooue basin in southeast Gabon.<br />

The occurrence of this species has been<br />

heavily affected by pollution of the<br />

waters in the vicinity of Franceville<br />

and deforestation leading to increased<br />

sedimentation.<br />

Aphyosemion schioetzi (Huber &<br />

Scheel 1981) is the only representative<br />

of the A. elegans group in the lower<br />

<strong>Congo</strong> to the north of the river. Its<br />

distribution is limited to an area measuring<br />

around 62 x 62 miles (100 x 100<br />

km), with the majority of known populations<br />

in the DRC and two (including<br />

the type locality) in the <strong>Congo</strong> Republic.<br />

We do not concur with many other<br />

authors that this species also occurs in<br />

the northern <strong>Congo</strong> with a distributional<br />

gap of more than 259 miles (400<br />

km) (see A. chauchei), but suggest that<br />

a further, probably still undescribed<br />

Aphyosemion species is involved, shown<br />

on the map as A. “schioetzi.” Aphyosemion<br />

schioetzi populations exhibit a<br />

relatively uniform color pattern, unlike<br />

the related species A. cognatum, in<br />

which numerous different phenotypes<br />

are known.<br />

Aphyosemion schoutedeni (Boulenger<br />

1920) has hitherto been assumed to<br />

be restricted to the type locality Medje,<br />

around 186 miles (300 km) northeast<br />

of Kisangani in the northeast of the<br />

DRC. Although the types are in good<br />

condition, all traces of coloration have<br />

disappeared. But to the present day,<br />

topotypes collected by Lang and Chapin<br />

in 1910 have retained their color pattern<br />

(Van der Zee & Huber 2006),<br />

which resembles that of A. castaneum<br />

except for the pattern of the anal fin.<br />

This color pattern is found in various<br />

RMCA Aphyosemion collections that<br />

originate from the Aruwimi basin east<br />

of the Kisangani-Buta road. Hence it<br />

can be assumed that the distribution<br />

region is significantly larger than previously<br />

thought.<br />

Taxonomy in upheaval: the genus Aphyosemion<br />

DNA studies indicate that the genus Aphyosemion is a complex assemblage<br />

of genetically clearly distinguishable species groups and isolated<br />

species. So far only the most obviously distinct species groups have<br />

been described as genera or subgenera (eg Chromaphyosemion, Kathetys,<br />

Diapteron, Episemion, Raddaella). On the other hand, right from<br />

the start the subgenus Mesoaphyosemion was the “rubbish bin” for all<br />

the difficult-to-classify species and species groups.<br />

And therein also lies a problem with the taxonomy of Aphyosemion<br />

s. l. Humans, as sight-oriented animals, can very easily appreciate the<br />

definition of Chromaphyosemion or Diapteron, as the species within<br />

these groups are very similar, but exhibit clear differences from other<br />

Aphyosemion. This is less apparent with other groups, for example<br />

the “A.” wildekampi and “A.” cameronense species groups. Molecular<br />

genetic studies indicate, however, that phylogenetically speaking, the<br />

visually very distinct species groups are not necessarily more genetically<br />

distant from one another.<br />

Now there are two taxonomic possibilities here: either accept<br />

that the other species groups also represent separate genera, just like<br />

Diapteron, Episemion, and others. Or put them all in a genus Aphyosemion<br />

s. l. with numerous subgenera. But that doesn’t solve the<br />

problem of the species groups so far without any name, whether as<br />

subgenus or genus.<br />

From a pragmatic viewpoint a catch-all genus Aphyosemion provides<br />

less information content than Diapteron or Chromaphyosemion,<br />

for example. For practical purposes it is all the same whether we use<br />

species-group names (e.g., the Aphyosemion bivittatum or A. georgia<br />

group) or scientific names (Chromaphyosemion, Diapteron) for the<br />

different groups. A species group equates to what some authors call<br />

either a subgenus or genus. Hence, as far as the aquarium hobby is<br />

concerned we can regard the terms “species group,” “subgenus,” and<br />

“genus” as essentially equivalent.<br />

Just as with the species groups, it is often the case at species level<br />

as well that usually the most distinctive species are described first. A<br />

good example is the A. cameronense species group or Mesoaphyosemion:<br />

populations are termed M. cameronense that do not have a particularly<br />

distinctive body coloration, that is, have metallic blue to blue-green on<br />

the sides of the body, overlain with a very variable red pattern. Several<br />

obviously different phenotypes have been described in recent decades,<br />