This article originally appeared in the June 1992 issue of Esquire. To read every Esquire story ever published, upgrade to All Access.

There’s a wonderful symmetry to the Gambino crime family. You can see this right away from two pictures of former bosses featured in the family photo album.

The first, which dates back to 1957, finds Albert “the Mad Hatter” Anastasia, his face still swathed in post-shave hot towels, permanently relaxed in a barbershop due to multiple bullet holes that were arranged by the family’s new patriarch, Carlo Gambino, who went on to enjoy a twenty-year reign.

The second, of more recent vintage, has Gambino’s brother-in-law Paul Castellano, anointed by Carlo on his deathbed to succeed him, stretched out on a sidewalk in front of a Manhattan steak house, also due to multiple bullet holes, orchestrated in this instance by yet another new Gambino family boss, John Gotti.

The irony here is that every time Gotti showed up at the family headquarters, the Ravenite Social Club on Mulberry Street in Little Italy, it was like having Anastasia in charge all over again. Anastasia had earned early renown as a grim reaper for the old Murder Inc., and Gotti achieved immediate recognition as a comer for dispatching an obviously certifiably committable kidnapper who picked a Gambino blood relative (for God’s sake!) to hold for ransom. Both bet heavily on horses and other sporting events and lost with regularity, which did little to improve their dispositions. “With Albert,” Joe Valachi once told me, “it was always kill, kill, kill.”

And John Gotti’s favored response, upon learning of an underling’s transgression, either real or imagined, was “whack him.” Gotti, it appears, was especially paranoiac about rats within the ranks. But as we know, it was Gotti’s most trusted sidekick, Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano, who did him in by turning government witness. Even granting that Sammy did not relish sharing a life in prison with Gotti, wiseguys to a man were left slack-jawed. The why, though, is very simple. Sammy cut himself the deal of the century. When, after all, did you last hear a fellow admit on the witness stand to nineteen murders and walk away? Sammy’s leverage was that the Feds, having twice before suffered Gotti thumbing his nose at them on the network news after failed prosecutions, would now do anything to nail down a conviction. So Sammy not only won’t have to worry about serving much time, but he gets to keep all his considerable cash, however ill-gotten.

As befitted the nation’s star hood, Gotti’s trial was like a rock concert. Deputized retired cops, manning walkie'talkies, were on hand to maintain order. General admission tickets had to be picked up in advance. Even reporters were required to stand in line for available seating. A half-dozen TV vans for satellite transmissions were a daily occurrence. Artists in court sketching the drama were warned not to include the faces of any jurors. Actors Mickey Rourke and Anthony Quinn dropped in to wish Gotti well. The big draw, of course, was the man himself, whose likeness had graced the covers of national magazines with breath less accounts of his double-breasted sartorial splendor, handcrafted shoes, and diamond pinky ring (we were advised, during the course of the trial, that he disdained the color green). The crush grew even greater when Sammy the Bull was sworn in. People began lining up outside the Brooklyn federal courthouse on March nights at 2:oo A.M. Eye contact between the two appeared to be a major item of reportage. The conclusions, depending on what paper you read, were yes, no, maybe. My personal observation was maybe ... once.

The funny part was that in the middle of all this, another racketeering trial was going on not a mile away across the East River in a Manhattan state criminal court, also involving the Gambino family, which would have far greater impact on Cosa Nostra operations than putting away five John Gottis.

Yet this courtroom had all the excitement of a mausoleum on a slow day. Besides judge and jury, prosecutors and defense attorneys and their clients, there was practically nobody else around. There were no fiery exchanges on either side. No quaint nicknames were to be heard. On the many secret recordings introduced into evidence, not once was a hint of mayhem of any sort voiced, of anyone facing the prospect of being whacked.

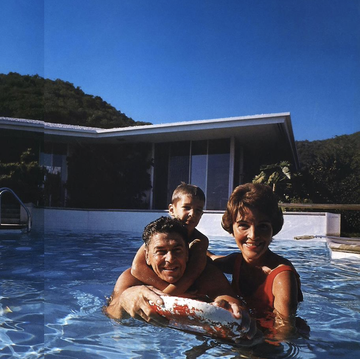

While John Gotti had been incarcerated from the moment of his indictment (for fear that jurors would be terrorized at the thought of him roaming about loose while they determined his fate), the chief defendants in this case emerged each morning from chauffeured cars in suits of sober gray. They had no past criminal convictions. Their names were Thomas Gambino and Joseph, his brother. Unlike Gotti, who never got past the eighth grade, Tommy was a graduate of Manhattan College and Joe had gone to New York University. Both had the deceptively mild-mannered way of their late father, Carlo, who in his latter days enjoyed nothing more than a bedtime snack of warm milk and graham crackers as he presided over what had become the country’s biggest crime family.

The charges brought by District Attorney Robert Morgenthau against the brothers Gambino were that they, along with another Cosa Nostra outfit, the Lucchese family, had a choke hold on New York’s multi-million-dollar Garment District. Morgenthau also had a novel idea. He not only desired to convict Tommy and Joe but to drive the mob out of the industry, “so we wouldn’t just end up with another Tommy.”

Old Carlo had bequeathed control of the Garment District to his sons. The Gambinos literally liked to keep things as much as possible in the family; Carlo’s wife was also his first cousin, and Tommy’s own wife, Phyllis, was the daughter of the late Thomas “Threefinger Brown” Lucchese. At the time of his indictment, Tommy Gambino, the dominant player, resided in a penthouse duplex just off Fifth Avenue, had a Long Island beach house, and was personally worth $100 million.

And who contributed mightily to this fortune? Well, mostly you and me, that’s who.

For every $100 we spent on a sport jacket or dress, including name labels like, say, Ralph Lauren or Liz Claiborne, a minimum of $3.50 and up to $7.50 went to the Gambinos and their cohorts. Trembling manufacturers simply passed on this “cost of doing business” to the consumer.

What the Gambinos and elements of the Lucchese family did was to divvy up and control all the trucking in the Garment District. Any one garment moves several times during the manufacturing process—from a fabric warehouse to the cutter, then the sewer, and onto where buttons, zippers, and so forth are added on. And nothing moved in any vehicle other than a Gambino or Lucchese truck. Tommy Gambino’s principal firm was called Consolidated Carriers. For a three-year period beginning in 1988, Consolidated took in $22 million. Tommy himself, along with brother Joe, drew a $1.8 million annual salary. Their 30 percent net-profit participation added another $2.8 million.

Naturally, Tommy’s uncle Paul Castellano, as the family boss, got his end—about $2 million a year. Indeed, the night Castellano went down, Tommy was on his way to join him for steaks. But once Gotti reassured himself that Tommy was not entertaining thoughts of challenge or vengeance (dumb, Tommy was not), he simply replaced Castellano as the new beneficiary of his unrivaled golden goose. Tommy would bring the money down to the Ravenite Social Club every Wednesday evening and hand it over to, of all people, Sammy the Bull.

D. A. Morgenthau’s chief of investigations, Mike Cherkasky, started things off by purchasing Chrystie Fashions, a dress manufacturer on the verge of bankruptcy. Taps and bugs were installed.

Right off, Cherkasky found out how free enterprise flourished in the Garment District. After getting trucking prices from Consolidated, he tried a Lucchese company, AAA Delivery.

“Say, where’d you say you’re located?”

“Chrystie Street.”

“Uh, we don’t do no pickups there. Call Consolidated.”

In their opening to the jury, Gambino attorneys sounded as though they might do well as stand-up comics. “The prosecution would love to have visions of gangsters dancing in your head and have you hear the theme from The Godfather . . . but Thomas and Joseph Gambino built their business the old-fashioned way. . . . Yes, Tommy is a friend of John Gotti’s, and they dined together and socialized just like any other friends would do. . . . You won’t find any baseball bats and broken bones in this case.”

At least the last part was true. The most threatening statement taped came from a pair of rather large Consolidated “salesmen” telling a cloak-and-suiter, “We’re from Tommy Gambino. You’re in Tommy’s building. You know who Tommy is?” According to Cherkasky, it was left to others in the industry to pass along certain verities: “You don’t go along, they’ll bust you up good.”

Morgenthau and Cherkasky were counting on Tommy’s fervent wish not to trade his penthouse for the slammer. The break came on a Sunday afternoon midway through the trial. Cherkasky was in Connecticut coaching a soccer team his eleven-year-old daughter was on. His beeper rang. It was the trial prosecutor, Eliot Spitzer. “They want to make a deal,” Spitzer said.

The initial offer was a $5 million fine and no jail, while allowing the Gambinos to stay in trucking.

All they got was no jail. The fine was $12 million—everything Consolidated Carriers had in its accounts. The Gambinos and the Lucchese interests had to get out of the garment trucking business within the New York metropolitan area. Most of the $12 million would be used to finance a special monitoring staff to ensure compliance. Any violations invited future prison sentences.

Tommy Gambino, of course, never would have dared copping a plea if John Gotti hadn’t been on trial himself for thirteen counts of murder and racketeering. Gotti learned about it in court when his lawyer gave him a copy of a press release revealing Tommy’s deal. His face contorted, he crumpled the paper in his fist and hurled it from him. There was nothing more he could do. Tommy had made a big bet that Gotti was soon to be permanently out of the picture, a winner as it turned out—and, all things considered, a small but still satisfying payback for the whacking out of Uncle Paul.