Easily overlooked, the second-generation M3 – identified by its chassis code, E36 – is now getting its due. Some enthusiasts fussed at the E36 M3 when it bowed in 1995, as BMW transitioned the M3 from a niche thoroughbred to a high-volume grand tourer. Other enthusiasts, like our friends at Car and Driver, named the M3 the best-handling car at any price in 1997.

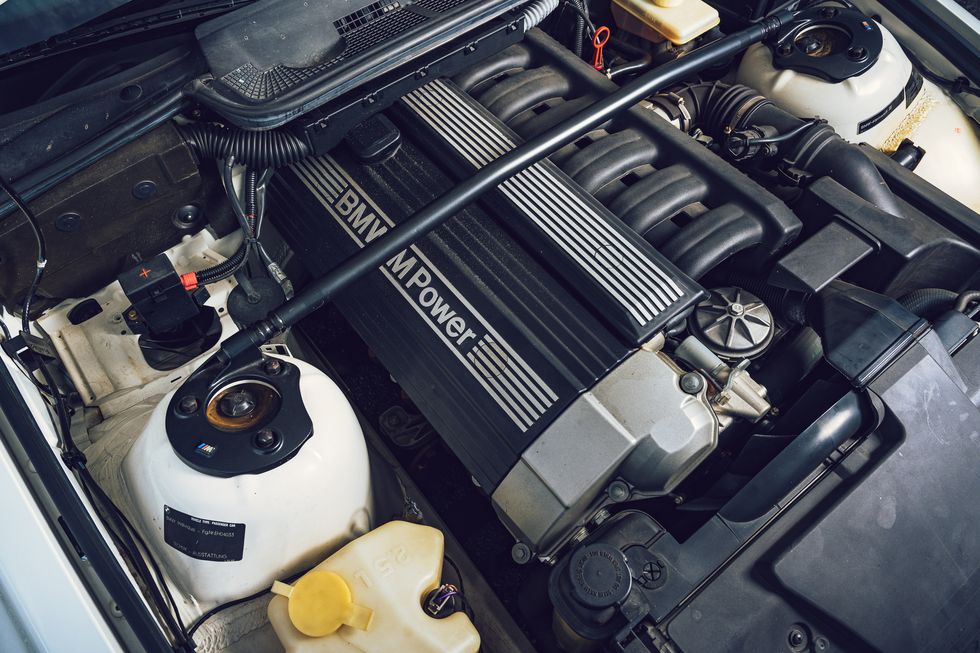

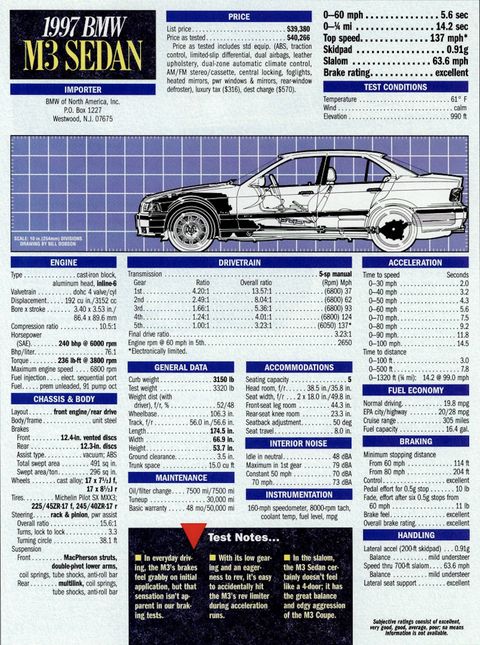

And the E36 remains divisive. Blessed with handling, but cursed by a lack of power. In the US market, a 240-hp, 3.0-liter straight-six replaced the E30’s buzzy four-banger. That 3.0-liter was bored and stroked to 3.2 liters by 1996, but both engines borrowed bones from the 325i’s pedestrian (but inherently excellent) 2.5-liter engine. When ‘Motor’ is the middle name of your company, shouldn’t the compact flagship get more grunt?

European cars did. They received a different engine entirely, an exotic strain of German voodoo equipped with sophisticated heads, individual throttle bodies, and a more-advanced variable valve timing system (VANOS in BMW parlance). Late versions of that engine put down 321 horsepower.

So for decades the E36 was underappreciated in America. At times, even scorned. Enthusiasts couldn’t forgive the weak US-spec engines. Then there were the other nits picked.

There were gripes about the E36 interior. The plastics, which cover a vast swath of the console, feel toylike next to the E30. Cheaper. Even the 1000-mile example we borrowed from BMW’s own museum had drooping door panel fabric. Then there are the glove boxes which are affixed to the dash by string cheese, the brittle plastic clips that turn your door panels into mariachi shakers, thin leather seat bolsters, and fifty other frustrations.

The E36’s swollen four-spoke steering didn’t maintain the delicacy of the E30’s three-spoke design. There are far more buttons in the E36s cabin, and overall, this M3 is a bit less elegant. But that’s fine. Just remember that the E36 is less delicate than the E30 and that’s central to its charm.

There’s more heft to nearly every input on the E36; a reassuring quality in operation. This E36 M3 left the factory a shade over 3200 lbs in most configurations, nearly 400 heavier than the compact E30. You feel most of those pounds, whether it’s less jostle from a pothole or worse body control when tossing the E36 through a chicane.

The steering wheel requires more shoulder to knife the E36 into a corner, and the shift lever’s action is notchier than the E30’s ‘box, but far more precise. The seats are great in this generation too with adjustment controls that all fall easily under your left hand, allowing manipulation of your seating position without higher brain function. Sure, they wear out but so does your brain if you use it too much,. When you’re trying to find that just-right setting during a warm-up lap at Mid-O, the quick seat adjustability is a godsend.

Some of these interior callouts sound like damnation by feigned praise. Not so. There’s plenty to love. Because at some point, you turn the damned key.

The S50 settles into a glass-smooth, Bimmer six signature idle. Prods at the throttle pedal reveal a free-revving engine that rasps and thunders up to a 6800 rpm redline. You sit low, wrapped bunker-like in the swept cabin, staring across that long hood. It’s a far more athletic driving position than in the upright E30, placing your hip close to the car’s center of gravity.

Rain came sprinkling down from low-hung clouds as I wheeled the E36 out onto Mid-Ohio’s curves. The fresh precipitation brought slick oils seeping from the asphalt, turning the track’s curves into banana peels. To pile on the mess, our E36 rode on the correct *cough* “period” tires, which you’d want on a museum piece. Less so on a track car.

Rather than diminish the M3’s spark, the ragged tires and oily surface highlighted the E36’s basic goodness. This generation’s longer wheelbase – paired with the low-grip track – emphasized this chassis’s penchant for slow, predictable, precise rotation. The S50 engine wailed at each corner exit before the 5-speed allowed quick, precise shifts. It felt effortless to break the car into perfect rhythm.

Like the E30, the E36 never feels fussy or knife-edged. There’s always room to trim and adjust cornering attitude with plenty of slack in the line should you get the car out of shape. Some of that is a lack of power; It’s harder to get a car bent out of shape when entering a corner 20 mph slower than its successors. But mostly the E36’s compliant and competent chassis shines through. It deserves those 1990s best-handling laurels.

Our test model was a special “Lightweight” variant sold in limited numbers for the North American market (BMW sold more than 71,000 E36 M3s globally, but just 125 lightweights). The Lightweight shed pounds by swapping in simple, mechanically operated fabric seats for the heavy leather units. It also used aluminum doors instead of stock steel, ditched sound deadening in the cabin, and went without A/C and a radio.

The bright shining cherry on top was that glorious tri-color flag livery draped across Alpine White paint.

In short, the LTW is like any other E36 M3 but more. It maintains the E36s perfect 50:50 weight distribution between the front and rear, and in the slower corners at Mid Ohio you’d swear this car rotates around the cupholder under your elbow.

An LTW, however, isn’t the only E36 M3 worth savoring. Any version of the car will do -- even the first-time-ever M3 sedans and convertibles. Because the aftermarket latched on to the E36 unlike any other M3. Around 10,000 of units of M3 shipped to North America, nearly twice the number of E30s. That allowed E36 M3s to enter the secondary market carrying massive depreciation and little wear.

For about a decade from 2004 on, E36 M3s could be had in great condition for $5000. That baseline has risen to $10,000 for a driver-quality car, but you’re still getting a world of opportunity for that money. An E36 fits into your life like a good Labrador – asking for an ounce of attention but rewarding with absolute fidelity. And they’re still the most affordable M3 today.

I owned several E36s as a college student and young adult. My buddies and I tinkered with them endlessly. We raced them, abused them, and generally pushed our luck through every blind gravel corner that arced through Eastern Washington’s wheat country. These are cars you can really live through. They are stout and indefatigable things.

For me, that’s the E36s enduring legacy – it functioned as a gateway drug for so many Americans who would’ve otherwise missed BMW and landed in a lesser import.

That accessibility created a demand for go-fast parts and a cottage industry catered specifically to this M3 chassis popped right up. Enthusiasts leveraged the E36s ubiquity – and considerable talents – to go road racing, rallying, and canyon carving. Even the neo-lowrider scene latched on to this chassis.

A few small tweaks can sharpen an E36 M3. A lighter exhaust, hotter camshafts and a less-restrictive intake manifold are de rigueur. Add to that some light engine tuning (usually in the form of a simple ECU chip), the right brake pads, and a set of springs. Now you’re a gold medal gymnast on Dancin’ With The Stars. You know you’re the best.

Whether or not you tune the car up, the E36 is a paragon of design virtue, if not a leap in overall quality. The E30 is dorky and lovable in 2021. The newer M3s are menacing, bordering on tryhard. We may be at peak Nineties nostalgia, but for me the E36 wears Goldilocks proportions – angular yet smooth, compact yet swept. Purely handsome. For reliability, usability, and carefree bliss, the E36 is hard to beat – even among this field of all-time greats.